A case for why both sides in the ‘reading wars’ debate are wrong – and a proposed solution

A case for why both sides in the ‘reading wars’ debate are wrong – and a proposed solution

By: Jeffrey S. Bowers, School of Psychological Science, University of Bristol and

Peter N. Bowers, WordWorks Literacy Centre, Kinston, Ontario.

This is an article published in the Washington Post but thought I would post here as well as well. Comments welcome!

You can also read the article at the Washington Post website by visiting this link

There are multiple comments and replies there.

How to best teach reading is one of the most controversial topics in education. The controversy concerns whether early instruction should focus letter-to-sound correspondences so that children can learn to sound out words (systematic phonics) or focus on the meanings of written words embedded in stories (whole language). This debate started decades ago and shows no signs of ending. What might not be so apparent to an outsider, however, is that there is near universal consensus in the research community that systematic phonics is the more effective approach. At this point, the controversy is largely between the research community and teachers in the classrooms who often prefer whole language.

As a parent or teacher, who should you trust? The sad truth is that both camps have it fundamentally wrong. As we show below, the so-called “reading wars” that pits systematic phonics against whole language has turned out to be a big distraction that has made it difficult for researchers and teachers to objectively look at the evidence and consider alternative approaches. After explaining why neither approach is supported by data or theory, we make the following proposal: Children should be taught how the English spelling system works (hint, it is not what you think).

What exactly is the debate?

As background, it is necessary to understand a bit about the similarities and difference between the two competing approaches. Systematic phonics explicitly teaches children letter-sound correspondences prior to emphasizing the meanings of written words. It is called systematic because it teaches letter-sound correspondences in a specific sequence as opposed to incidentally or on a ‘when-needed’ basis. Several versions of systematic phonics exist, but the most common version (the version mandated in the UK) is called synthetic systematic phonics, and it teaches children the sound of letters in isolation and then coaches students to blend the sounds together. For example, a child might be taught to break up the written word <dog> into its component letters, pronounce each letter in turn—/d/, /ɔ/, /g/— then blend them together to form the spoken word “dog”.

By contrast, whole language primarily focuses on the meaning of words presented in text. Teachers are expected to provide a literacy rich environment for their students and to combine speaking, listening, reading, and writing. Students are taught to use critical thinking strategies and to use context to guess words that they do not recognize. What also needs to be emphasized is that whole language typically includes some phonics, but the phonics is unsystematic (e.g., children are taught to sound out words when they cannot guess the word from context). For example, the authors of the National Reading Panel (2000) who strongly endorse systematic phonics, note:

Whole language teachers typically provide some instruction in phonics, usually as part of invented spelling activities or through the use of graphophonemic prompts during reading (Routman, 1996). However, their approach is to teach it unsystematically and incidentally in context as the need arises. The whole language approach regards letter-sound correspondences, referred to as graphophonemics, as just one of three cueing systems (the others being semantic/meaning cues and syntactic/language cues) that are used to read and write text. Whole language teachers believe that phonics instruction should be integrated into meaningful reading, writing, listening, ands peaking activities and taught incidentally when they perceive it is needed. As children attempt to use written language for communication, they will discover naturally that they need to know about letter-sound relationships and how letters function in reading and writing. When this need becomes evident, teachers are expected to respond by providing the instruction.

So the reading wars debate is not about whether or not children need to learn about letter-sound correspondences. Rather, it is about how and when these correspondences should be taught, and in what context. According to proponents of systematic phonics, letter-sound correspondences need to be taught systematically and first as this provides the means by which meaning can be accessed from written words. By contrast, according to the proponents of whole language, meaning plays an essential role in reading instruction from the start. On this later approach, a combination of meaning-based instruction with unsystematic phonics is the more effective method. So who is right?

Advocates of phonics can point to multiple “meta-analyses” that synthesize the results of dozens of studies, thousands of academic articles, and numerous popular books that all strongly endorse systematic phonics. For example, the authors of the most influential document in support of systematic phonics, the National Reading Panel (2000), conclude:

“Students taught systematic phonics outperformed students who were taught a variety of nonsystematic or non-phonics programs, including basal programs, whole language approaches, and whole word programs. (p. 2-134)”.

Similarly, The Rose Report that led to the legal requirement to teach systematic phonics in English state schools concludes:

“Having considered a wide range of evidence, the review has concluded that the case for systematic phonic work is overwhelming …” (Rose, 2006, p. 20).

Daniel Willingham, who recently published in this same blog, wrote the following in his book entitled “Raising Kids Who Read: What Parents and Teachers Can Do”:

“… there are few topics in educational psychology that have been more thoroughly studied, and for which the data are clearer… it’s clear that virtually all kids benefit from explicit instruction in the [letter-sound] code, and that such instruction is crucial for children who come to school with weak oral language skills”. (2015, p. 124).

The neuroscientist Stanislas Dehaene claims that the evidence proves phonics is better than alternative methods, writing:

It should be clear that I am advocating here a strong ‘phonics’ approach to teaching, and against a whole-word or whole-language approach… theoretical and laboratory-based arguments converge with school-based studies that prove the inferiority of the whole-word approach in bringing about fast improvements in reading acquisition. (Dehaene, 2011, p. 26).

Given all this, how can we responsibly challenge the evidence taken to provide strong support for systematic phonics? As we show below, when the empirical evidence is viewed dispassionately rather than as a weapon in the reading wars, the case for systematic phonics quickly unravels.

A quick review of the empirical evidence

First, consider the National Reading Panel (2000) meta-analysis that combined the results from 38 published experiments that compared various methods of reading instruction. This report continues to be the most cited document in support of systematic phonics over whole language, but a careful reading of the document reveals that it did not even test this hypothesis. We need to get a bit technical here to explain why this is the case, but it is important to understand this point as it undermines the most important evidence in support of systematic phonics.

Here is a quote from the National Reading Panel that describes the design of the study:

“…findings provided solid support for the conclusion that systematic phonics instruction makes a more significant contribution to children’s growth in reading than do alternative programs providing unsystematic or no phonics instruction [bold added] (NRP, 2000, p. 2-132).:

The bold highlights the key point that systematic phonics was compared to a control condition that combined two separate conditions, namely, (1) intervention studies that included unsystematic phonics and (2) intervention studies that included no phonics. Where does whole language fit into this meta-analysis? Whole language was just one of many alternatives programme that were merged together into a single control condition. Specifically, the whole language interventions were combined with “balanced literacy”, “whole word”, and other forms of alternative programs that included unsystematic or no phonics. The key finding from the National Reading Panel was that systematic phonics was more effective than the average performance in the control group that included various forms of reading instruction. As elementary point of logic, if you compare systematic phonics to a mixture of different alternative methods, only a subset of which are whole language, then you have not tested systematic phonics compared to whole language.

More importantly, when Camilli et al. (2006) reanalyzed the National Reading Panel (2000) dataset and directly compared systematic to unsystematic phonics (excluding studies that had no phonics, such as “whole word” interventions), the advantage for systematic phonics was greatly reduced, and no longer statistically significant. This undermines the claim that systematic phonics is more effective than whole language instruction that includes unsystematic phonics. Nevertheless, this finding has largely been ignored. The National Reading Panel has been cited will over 22,000 times, and over 2000 times since 2017. By contrast, the Camilli et al. (2006) paper has been cited a total of 58 times, and only 9 times since 2017 (with 3 of these citations coming from us).

This conceptual confusion persists. Bowers (2018) shows that every subsequent meta-analysis taken to support systematics phonics over whole language has made the same mistake of comparing systematic phonics to a mixture of different methods, or comparing systematic phonics to interventions that included no phonics. Accordingly, none of these meta-analyses should be taken to support systematic phonics over whole language. Moreover, Bowers (2018) points out a host of additional fundamental problems with these meta-analyses that further undermine this conclusion. There really is little or no empirical evidence to support the conclusion that systematic phonics is best practice. The fact that this claim is repeated 1000s of times in the literature does not make it so. But it is somewhat of a scandal that the research is so consistently misrepresented in the literature.

This is no victory for whole language either. The two approaches appear to be equally good (or bad) at improving reading in schools. If you are not happy with the outcomes of whole language, you should similarly be unhappy with the outcomes of systematic phonics, and vice versa. This is the conclusion we draw, and we hope it motivates researchers and teachers to consider alternative methods of reading in the US (where whole language is still commonplace), in England (where systematic phonics has been the norm since 2006), and every other English-speaking country.

What about the theoretical motivation for systematic phonics?

Proponents of systematic phonics also appeal to theory in support of their approach. Indeed, they are quick to ridicule the theoretical motivation for whole language, and with good reason. According to foundational theory for whole language, learning to read is just like learning to speak (Goodman, 1967). Given that virtually everyone from every culture learns to speak without any formal instruction in a context of being exposed to meaningful speech, it is concluded that children should learn to read in the same way, naturally, by reading meaningful text. The fact that not all verbal children learn to read with whole language should be a first clue that something is wrong with this theory.

But the theory for phonics also is fundamentally flawed. The standard claim is that English is an “alphabetic system” in which letters represent sounds, and this in turns motivates systematic phonics given that it teaches these letter-to-sound mappings. On this view, it is just an unfortunate fact that the English spelling system includes so many exception words (or “sight words”). The linguist David Crystal (2003) estimates that the phonics can only explain about 50% of English spellings. Question: Why is there a <g> in <sign>? Why is it <dogs> with an <s> rather than *<dogz> with a <z> given that we pronounce <dogs> with a /z/? Why is <does> spelled as it is instead of *<duz>? Why is it <Christmas> not <Chrismas>? Answer: Because English spellings are crazy. How should children learn these exception words? Remember them by rote. In response to the crazy system, some proponents of systematic phonics use “decodable texts” that are composed of regular words, leaving all the irregular words (e.g., dogs, does, because, two, here, gone, action, jumped, Christmas, etc.), and all the wonderful children’s books, for later.

However, the fact that there are so many exceptions suggests that there might be something wrong with the alphabetic principle. And there is. Linguists have long known that the letters in words represent more than sounds. Rather, the English spelling system is designed to represent both the sounds (phonemes) and the meaning (morphology) of words. As the famous linguist Venezky (1967) put it:

“The simple fact is that the present orthography is not merely a letter-to-sound system riddled with imperfections, but instead, a more complex and more regular relationship wherein phoneme and morpheme share leading roles”.

Perhaps the most straightforward sign that there is something wrong with alphabetic principle is the observation that most homophones (words with the same pronunciation but with different meanings) are spelt differently (e.g., <to>, <two>, <too>). If English followed the alphabetic principle, then the obvious prediction is that most homophones should be spelt the same way. How to explain the failed prediction? Should we just shrug our shoulders and conclude that this is one of those cases in which the (many) exceptions prove the principle? Let us suggest another possibility, consistent with Venezky, namely, English spellings encode the interrelationship between sound and meaning. On this hypothesis, the different spellings of homophones mark the fact that the words have different meanings.

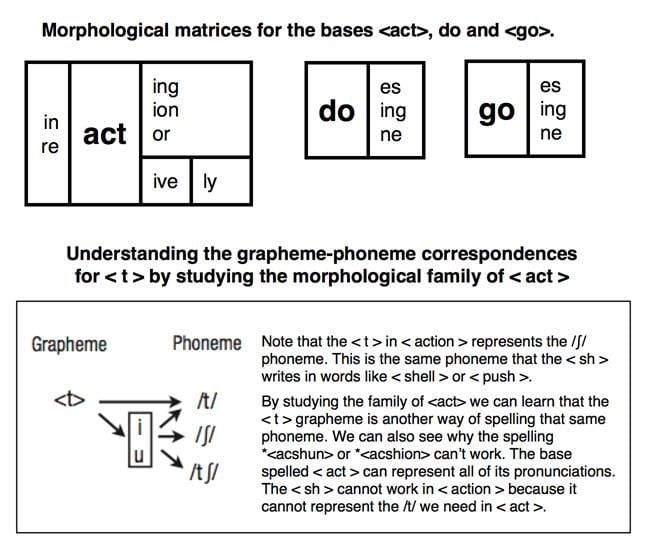

Very briefly, to illustrate how the English spelling system encodes meaning, consider the morphological families associated with the bases <act>, <do>, and <go> in the Figure below. The key point to note is that the spellings of the bases are consistent across all members of the morphological families despite pronunciation shifts (e.g., acting vs. action; do vs. does; go vs. gone). Similarly, note the consistent spelling of the <-ed> suffix in <jumped>, <played>, and <painted> despite the fact that <-ed> is associated with the pronunciations /t/, /d/ and /əd/, respectively. The spellings of <action>, <does> and <gone> make sense once you understand that spellings also encode the meaning.

These are not cherry-picked examples. As the linguists Venezky (1967) and Carol Chomsky (1970) explained, English prioritizes the consistent spelling of morphemes over the consistent spellings of phonemes. This is true for words that occur in adult novels and children storybooks that both include of a high percentage of morphologically complex words (Bowers & Bowers, 2018b). A language that prioritizes the consistent spelling of morphemes over phonemes is not following the alphabetic principle, and it raises questions about teaching methods that ignore this structure. Once you understand the English spelling system, it makes no sense to consider <goes> regular and <does> irregular, as claimed with systematic phonics.

Our proposal

We expect teachers of physics, mathematics, biology, etc. to understand the basics of physics mathematics, and biology. Here is our proposal: Teachers should know the rules of the English writing system when teaching children to read and write English. Children can be taught letter-sound correspondences AND the regular way that morphemes are spelt. This does not need to be complex at the start: Children can learn why the words <dogs> and <cats> have the letter <s> at the end despite the different sounds at the end. Children can study relevant words organized in morphological families (as in the matrices above) so that they learn how words are related to one another, both in spelling and meaning, in order to improve their reading, spelling, and vocabulary.

Structured Word Inquiry (Bowers & Kirby, 2010) is an instructional that approach that teaches morphological families with the help of the matrix and explicitly teaches letter-sound (grapheme-phoneme) correspondences in that context, as well as historical (etymological) influences that make sense of spellings. Proponents of both systematic phonics and whole language can find central aspects of their instruction in structured word inquiry. Like systematic phonics, this approach breaks down words into parts, but rather than just focusing on one set of regularities (letter-sound correspondences) it highlights all regularities (including the fact that morphemes are spelt consistently, and the way that morphemes are combined in regular ways). And consistent with whole language, it emphasizes the importance of meaning from the start with the aim of making early reading instruction interesting, but it focuses on meaning words rather than text.

But structured word inquiry does not simply combine aspects of phonics and whole language. Rather, it is built on the insight that the English spelling system is logical and makes sense, and that children can learn the system by testing simple hypotheses about words – much like learning other scientific disciplines. Unlike systematic phonics and whole language that provide little or no explanation for most sight words, children can learn why a word is spelt the way it is, learn how letter-sound correspondences occur within morphemes, and learn how morphologically related words share spellings and meaning. Nothing motivates learning like understanding.

Our proposal is not mere speculation. There is preliminary evidence that teaching morphology and the logic of the writing system is effective for initial reading instruction, as summarized by Bowers and Bowers (2017). But it has to be acknowledged that the data for our proposal is limited. In large part, this is because there has been so much focus on the phonics vs. whole language debate that few researchers have considered alternative approaches. It is long past time to move beyond the reading wars and explore the possibility that children should be taught the meaningful and logical organization of their writing systems. Parents might learn something too.

If you would like more information, here are some resources you can access for free. For a short introduction to the English spelling system and how to teach it we recommend the following paper recent published in the journal “Current Directions in Psychological Science” that you can download here (Bowers and Bowers, 2018a; https://cpb-eu-w2.wpmucdn.com/blogs.bristol.ac.uk/dist/b/403/files/2018/04/bowers-and-bowers-in-press.pdf). For a more detailed argument why instruction should include morphology from the start of instruction download the following paper (Bowers and Bowers, 2018b; https://psyarxiv.com/zg6wr/). For detailed critique of the (non) evidence for systematic phonics, see Bowers (2018; https://psyarxiv.com/xz4yn/). Go to the following link for a number of blogposts on these topics: https://jeffbowers.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/blog/. To see some YouTube videos illustrating Structured Word Inquiry in in classrooms see thus YouTube page: https://www.youtube.com/user/WordWorksKingston:. And follow us on twitter! @jeffrey_bowers and @borneo_pete

References

- Bowers, J.S. (2018). Reconsidering the evidence that systematic phonics is more effective than alternative methods of reading instruction. PsyArXiv.https://psyarxiv.com/xz4yn/

- Bowers, J.S., and Bowers, P.N. (2018a). Progress in reading instruction requires a better understanding of the English spelling system Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27, 407-412.

- Bowers, J.S. & Bowers, P.N. (2018b). There is no evidence to support the hypothesis that systematic phonics should precede morphological instruction: Response to Rastle and colleagues. PsyArXiv. https://psyarxiv.com/zg6wr/

- Bowers, J.S., & Bowers, P.N. (2017). Beyond Phonics: The Case for Teaching Children the Logic of the English Spelling System. Educational Psychologist, 52, 124–141.

- Bowers, P. N., & Kirby, J. R. (2010). Effects of morphological instruction on vocabulary acquisition. Reading and Writing, 23, 515-537.

- Camilli, G., Vargas, S., & Yurecko, M. (2003). Teaching children to read: The fragile link between science & federal education policy. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 11, 15.

- Camilli, G., M. Wolfe, P., & Smith, M. L. (2006). Meta-analysis and reading policy: Perspectives on teaching children to read. The Elementary School Journal, 107(1), 27-36.

- Chomsky, C. (1970). Reading, writing, and phonology. Harvard Educa- tional Review, 40, 287–309. 10.17763/haer.40.2.y7u0242x76w05624

- Crystal, D. (2003). The Cambridge encyclopedia of the English language (2nd Edition). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Dehaene, S. (2011). The massive impact of literacy on the brain and its consequences for education. Human Neuroplasticity and Education (Vatican City), 117, 19 –32.

- Goodman, K. S. (1967). A psycholinguistic guessing game. Journal of the Reading Specialist. 6, 126–135.

- National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction.

- Rose, J. (2006) Independent Review of the Teaching of Early Reading. Nottingham: DfES Publications

- Seidenberg, M. (2017). Language at the Speed of Sight: How we Read, Why so Many Can’t, and what can be done about it. Basic Books.

- Venezky, R. L. (1967). English orthography: Its graphical structure and its relation to sound. Reading Research Quarterly, 75-105.

- Willingham, D. T. (2015). Raising kids who read: What parents and teachers can do. John Wiley & Sons.

That’s a really insightful breakdown of the debate. It’s interesting how the gap exists not just between different methods, but between research and practice. Bridging that disconnect—so that evidence-based approaches like systematic phonics are better supported and understood in classrooms—seems like a crucial next step.

That’s so true! It’s fascinating how our brains work—once we become aware of something, we suddenly notice it everywhere. It’s a great reminder of how perception and attention shape our experiences.

I absolutely agree that morphology and English spelling rules must be explicitly taught to students. That’s why structured literacy instruction is necessary. The Science of Reading is a term that represents cognitive science in reading. Structured literacy instruction goes far beyond only teaching synthetic phonics; it also goes beyond teaching morphology and spelling rules. Discussion and promotion of it is important especially as a pathway to end the Reading Wars.

Thank you, Jeff and Pete, for your scholarship. As a Reading Specialist who works regularly with dyslexic readers, I can say that the approach that you have pioneered, Structured Word Inquiry, has literally changed the reading achievement trajectory of my students. Many struggling readers exhibit a difficulty with accurately decoding words. They may omit or substitute letters and word parts which results in low accuracy rate (the percentage of words read correctly). In the lower grades, these students may have enough background knowledge to have good comprehension but as they reach 4th grade, this low accuracy rate significantly impedes comprehension as text becomes more sophisticated and student background knowledge drops as they encounter more content-based texts. Structured Word Inquiry deeply focuses student attention on both the phonology and morphology of words using a systematic framework of 4 questions. SWI also focuses student attention on the etymology, or history, of words, This allows students to understand why words are spelled the way they are and that is powerful because students start to understand, for themselves, the English spelling system. Not only do they understand the spelling system, they develop the framework to independently learn about any word they so choose. It has been so powerful to see students develop confidence as they improve decoding and meet or exceed grade-level expectations in comprehension, spelling and vocabulary. If you are interested in learning more about this, Pete Bowers website (http://www.wordworkskingston.com) and his book, “Teaching How the Written Word Works” will get you started!

I’m so glad to hear of your experience working with SWI Mona. I want to highlight this section of your message, in which you argue that your work with SWI “… allows students to understand why words are spelled the way they are and that is powerful because students start to understand, for themselves, the English spelling system. Not only do they understand the spelling system, they develop the framework to independently learn about any word they so choose.”

The generative learning you describe is the kind of learning we expect from any sort of scientific inquiry. Whatever domain we are in, if we subject our hypotheses to falsification, we begin to shed misunderstandings, and bring greater precision to our understanding of how that domain works. In the case of SWI, not just students, but teachers continue to deepen their understanding of orthographic structures and conventions, and of the processes by which to investigate them.

This is one reason it can be so hard for people just looking at SWI from outside before diving in themselves. The terminology, linguistic tools etc. are all so new and different. It can appear to be too complex for adults let alone students. But it doesn’t take long before new concepts introduce new understanding and then become normalized. Each new understanding can lead to understanding of ever deeper concepts. Once instruction highlights real structures (e.g. morphemic and graphemes) in a complex system, learners can’t help but notice those structures and thus encourage the asking of new questions to investigate. When teachers work in this way for a couple of years, what used to seem confusing becomes easy (like learning a new language) and their ability to share that understanding with students grows as well. Similarly, students who learn in a school in which teachers who reflect how orthography works from the start, ideas which can seem way advanced for adults, end up being everyday for young students.

Scientific inquiry is a process of noticing interesting things and testing them out. The way we use word sums in SWI with “spelling-out-loud” and “writing-out-loud” word sums forces students and teachers to identify not only the written morphemes in relate words, it brings the expectation of identifying graphemes and orthographic markers in the base. Teachers and students announce and write out graphemes all the time. The word “teaching” would be spelled out “t – ea – ch —- ing” to ensure that the child has the three graphemes in the base “teach” highlighted, and the “-ing” suffix. The graphemes are confirmed by linking to their phonemes. Now all of those graphemes and morphemes have been planted and ready to be encountered in other words. A student may notice (or the teacher may plant) the word “health” to see if children recognize a digraph they’ve encountered. But in this word we see that the “ea” is not spelling the phoneme we see it spell in “teach”. But if we follow the 4 questions, we would get from the word “health” to its base “heal” where we do see that same pronunciation. And now we might look for more evidence of the “-th” suffix or more word families where the “ea” represents different pronunciations. Each orthographic concept learned leads to others.

We are all familiar with the experience of having something new pointed out to us one day, and then all of a sudden we see it everywhere. I remember seeing my first add for this new hybrid car, the Prius. That week I kept seeing them. Of course it was not that I was suddenly exposed to more Priuses than the week before, but now that I had been primed (by advertising) to see them, I was more likely to take note of them.

Anyone interested in how that process links to SWI, I have a Newsletter on that topic at this link: https://tinyurl.com/structure-is-freeing

Thanks Mona for sharing your story.

Pete and Jeff, what do you think of the Alphablocks videos as a “way in” to help students recognize the letters that can represent sounds? My struggling first graders love these videos.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ROKNNvuGpEo&t=191s

Jeff, in reading Rastle and Taylor’s response a year ago to your propsal as stated above that “children can study relevant words organized in morphological families (as in the matrices above) so that they learn how words are related to one another, both in spelling and meaning, in order to improve their reading, spelling, and vocabulary” they write:

“Instruction on its own does not yield long-term knowledge. Instead, this is likely to arise over time through repeated experiences with a particular structure (e.g., suffix -er occurring repeatedly in the context of agentive nouns such as teacher, builder,

banker; see, for example, Nation, 2017; Tamminen, Davis, & Rastle, 2015). Furthermore, some theories of reading acquisition suggest that prior knowledge of stems may be a critical factor in the acquisition of morphological (affix) representations (Davis, 1999). Based on this evidence, we would argue that devoting time in the initial periods of reading instruction to interactions between phonology, morphology, and etymology may be ineffective since it will be unsupported by the text experiences of the child. It

is also likely to decrease the time available for instruction relevant to spelling-sound knowledge (Taylor et al., 2017). Such instruction is critical for learning the single-morpheme stems at the foundation of morphological families (e.g., the “act” in action, activate, react).”

This year I mostly work with struggling readers, but I also job share one day a week and teach in a third grade classroom. I realiaze this is just anecdotal evidence, but I do see first-hand how my non-readers in my intervention groups struggle to read the single-morpheme stems like “act” and how by contrast my third graders can tackle the morphological families like action, activate, and react. I can also relate to the statement of how much time it takes helping these non-readers read these single-morpheme stems, which is why so many of us favor laying this foundation for beginning readers through an emphasis on “phonology first”.

I don’t understand the point the authors are making in this quote. SWI will teach many morphological families that include the -er suffix. Children will also read texts. The one thing we know more than anything is that learning and memory is best for information that is studies in a meaningful manner, especially when the information is well organized. Children do know about affixes before instruction, and they will be explicitly taught how affixes are represented in the orthography.

I’m not convinced that children struggling with phonics need more phonics. The empirical evidence I review does not support this conclusion. Why not combine GPCs with meaning and vocabulary instruction to make it more engaging for child. Children that struggle with phonics often have phonological deficit. Including more meaning might help.

Harriet

When I worked as a voluntary reading assistant in a primary school some years ago, I first established with a very short test how well the pupils knew basic English letter to sound rules and addressed any gaps in their knowledge with practising short word lists like hatch, latch, pach, sigh, sight, fright and boon, broom, croon.

I also listened to them read a bit from their current reading book and made a note of words they struggled with, stopping when I had noted 6 or 7 (e.g. wanted, know, don’t, what, near, tough, one). We then looked at them again and I then wrote simpler spellings for them next to them, which they could read easily:

Wanted wonted

Know no

Don’t doant

With a big gap between the columns, we could fold the paper so the normal spellings were on top for learning at home, with the simpler ones underneath, to be looked at if stuck. I knew that these children were getting no help with learning to read at home, so wanted to make them more able to help themselves. It worked beautifully. (But that is a claim that all proponents of new ideas make…). I got the idea from knowing that the Chinese have solved their enormous literacy problems pre 1958 by teaching children to read alphabetically spelt Chinese first and then using it for learning to read the traditional characters https://literacyproblems.blogspot.com/2018/03/spelling-systems-literacy-learning.html

What I found most noticeable was that most reading problems were caused by irregular spellings in what u call ‘single-stem morphemes’, or what I call ‘root words’ in my work.

Jeff, what do you think of this recommendation in Rastle’s “The Place of Morphology in Learning to Read English.” She writes:

Thus, morphological regularities are not relevant to the overwhelming proportion of tokens experienced in the first year of reading instruction. Of those words that comprise more than one morpheme, 86% contain the suffixes ‘-ed’ or ‘-s’ that attach to stems (Masterson et al., 2010). Thus, Masterson et al. (2010) argued that instruction on this limited set of suffixes may be appropriate during this period. This recommendation is broadly consistent with the approach to reading instruction in England, where the National Curriculum specifies that alongside systematic phonics, simple suffixes such as ‘-s’, ‘-er’, ‘-ing’, ‘-ed’ should be taught as part of the reading and spelling curriculum by the conclusion of 1st grade (when children are 5 or 6). The English National Curriculum then advances during the later years of primary school to higher-level morphological regularities that include a wide range of prefixes and suffixes, their functions or meanings, and any relevant spelling rules pertaining to their use (Department for Education, 2014). Further corpus analyses would be needed to assess how well this approach to morphological instruction supports the texts that children of different ages are reading and using to practice their reading skills; and ultimately, the evaluation of any reading method should be subject to empirical evidence.

In particular, I am currently experiencing with my first grade intervention groups the following recommendation regarding adding simple suffixes to reading instruction:

“This recommendation is broadly consistent with the approach to reading instruction in England, where the National Curriculum specifies that alongside systematic phonics, simple suffixes such as ‘-s’, ‘-er’, ‘-ing’, ‘-ed’ should be taught as part of the reading and spelling curriculum by the conclusion of 1st grade.”

At the beginning of the year, my 24 struggling first graders were for the most part non-readers. As part of my program, I send home the 10 phonics books from our old reading program for students to read to a “print partner”. Now that many of these students are on books 9 and 10, I was reminded yesterday as one child read to the group to earn his prize and go on to the next level that the emphasis in this series has definitely progressd from “cracking the code” with those pesky vowel teams to practicing these spelling patterns by also practicing suffixes (groaning, feeling, stooping, lighting, trained, flowed, spoiled, etc.).

I realize that you have addressed these points numerous times elsewhere (so I really don’t expect you to keep repeating yourself), and we are all in agreement that we await more rigorous research, but I did want to point out that as I work with my 45 struggling first and second graders on a daily basis, I am constantly questioning my methods, and so far I find that recommendations from researchers like Rastle (who do indeed emphasize the importance of morphology) regarding the timing of morphological instruction are most in line with what I experience working with struggling readers.

Finally, I teach one day a week in a third grade classroom, and I now pay far more attention to morphology than I used to. So that is a definite benefit that real students in a real classroom have had from this ongoing discussion (disagreement?).

Harriett, I’m glad to hear that you are finding value in increasing your attention to morphology than you used to, and that you feel these discussions have been helpful.

I’m sure that what you experience with your Grade 1 students is common. And I’m fine with that. When I do workshops, I always try to emphasize that no-one should stop doing what they are doing that they find valuable for their students’ learning because they attended a 1-, 2- or 3-day workshop. What I suggest is that if something they learned from their workshop offered them understanding about spellings that they previously did not know, that is all the evidence that the need to know that there is something about the work in SWI that is worth exploring. As their own understanding grows over time, they get to decide for themselves what they are comfortable dropping from their practice, what they add and what they change.

A favourite story of mine to illustrate this point is about a reading specialist who was very well trained in Slingerland (I understand it is like Orton-Gillingham but for the classroom) and did tons of work as a reading specialist with young and very dyslexic kids. We’ve become great friends, but when I first met her at her school, her first impression was that what I was doing was just not appropriate for dyslexic kids. But I kept returning to her school and she kept coming to workshops and studying. She then moved into a Grade 1 classroom and was astonished at the effectiveness of asking kids to “spell-out” words when they got stuck compared to “sound it out”. That got her digging more and she then brought colleagues to study more and more. About 4 years after our first meeting she came to a 4-day workshop with me. At the end, I asked her what she thought she got out of that session that was new compared to the multiple workshops she’d attended with me each year. I loved her response. She said, “I think I’m finally able to drop practices that I thought I’d never drop.” But notice, Harriett, this was after 4 years of intense study with me and others and working with her kids in light of that study.

Similarly, another good friend who is a brilliant pre-school teacher tells the story that when I first came to her school she complained to her principal, “Why would I go to a spelling workshop? I teach pre-school!” But she let me come in her class, she was surprised by and interested in what she saw her kids do and she came to the workshop, and then she worked hard over the years — every year finding she could go deeper into orthography than she ever though possible in the beginning. She now complains that pre-school is too late as she has to unteach things like “the s sound” and the “z sound”.

What I’d like you to consider is how long you have studied and practiced in the ways that you feel more comfortable with in your Grade 1 class. Now contrast that with the nature of the study and time you’ve spent with SWI. I’m sure you have taken years of intense study and practice in what you are now most comfortable with in your classroom. There is no way that I would expect anyone to develop a deep understanding of SWI in blog post discussions, reading some articles and trying some things in class. And I don’t expect you to make drastic changes to your practice based on that. But what I do hope is that you won’t draw hard conclusions about SWI before you’ve given it serious study with people who understand it, and tried it in your classroom over time. There is no hurry. I would not recommend you drop what you are doing and dive into something that you have not been able to study closely.

Some will dabble with SWI and integrate it to some degree, some will leave it behind and some will go deeper every year.

If you happen to be within striking distance of San Francisco, I do recommend you consider attending the 5-day Nueva SWI Institute I run there starting June 17. At that institute you study not just with me, but with Nueva teachers from pre-school to Grade 5 who have been working intensely with SWI for years now. You can see information on that here: https://www.nuevaschool.org/conferences-institutes/structured-word

Some time ago I wrote a piece trying to address this question of “How do I integrate SWI with my current practices?” I encourage you to consider that piece at this link:

http://www.realspellers.org/resources/wordworks-newsletters/1353-ww-special-publication-how-do-i-integrate-swi-with-my-other-literacy-instruction-practices

Cheers,

Pete

Thanks, Pete. I will definitely pursue your links. In the meantime, if you haven’t read this piece– EPS mid-career prize lecture 2017: Writing systems, reading, and language, Kathleen Rastle, First Published February 15, 2019–I highly recommend it.

“I have argued that the acquisition of spelling–sound knowledge is necessary in reading acquisition in alphabetic writing systems, but that it is unlikely that this knowledge alone could support skilled, silent reading in English. Instead, contemporary theories of skilled reading propose that readers must also acquire a direct mapping between printed words and their meanings (e.g., Coltheart et al., 2001; Harm & Seidenberg, 2004; Woollams et al., 2007). This direct mapping is represented in ventral pathway brain regions (Taylor et al., 2013), which become increasingly tuned to printed words as readers develop greater skill (Dehaene-Lambertz, Monzalvo, & Dehaene, 2018) certainly into the period of adolescence (Ben-Shachar, Dougherty, Deutsch, & Wandell, 2011). Much less is known about the acquisition of direct links between spelling and meaning, but it is thought that this process of “orthographic learning” arises through an accumulation of experience with printed text (e.g., Castles & Nation, 2006; Nation, 2017), as a child uses their spelling–sound knowledge as a self-teaching device (Share, 1995). The self-teaching theory proposes that successful, repeated decoding of an unfamiliar word into a spoken language representation provides a mechanism through which to establish the orthographic lexical representations necessary for rapid word recognition (Share, 1995).”

The original English spelling system (devised by monastic scribes in Canterbury in the 7th C) was as alphabetic as most Latin-based systems, but it has been repeatedly changed since http://englishspellingproblems.blogspot.co.uk/2012/12/history-of-english-spelling.html. At word level, over half now no longer apply the basic English spelling rules http://englishspellingproblems.blogspot.co.uk/2015/01/the-english-spelling-system.html completely https://literacyproblems.blogspot.com/2017/12/regularirregular-spellings-in-7000-words.html But at phoneme level, around 80% of English spellings are still regular, because in most words with irregular spellings only one phoneme is spelt irregularly (e.g. frIEnd, hEAd, mOther), with only a few like ‘pheasant’. In that sense English spelling still obeys the alphetic principle (of using letters to represent speech sounds in a regular manner) quite closely.

The 335 words http://englishspellingproblems.blogspot.co.uk/2013/02/homophones-with-different-spellings.html which are deliberately spelt differently for different meanings (here/hear, their/there) are a deliberate departure from the alphabetic principle. They are needless, because 1) their identical pronunciations never cause any problems in speech and 2) over 2,000 English words cause no difficulties by having just one spelling for different meanings (mean, lean, found, sound, bank, tank …).

One thing is absolutely certain: spellings which disobey the alphabetic principle make learning to read and write far more difficult than those that do. Countries which have orthographies which obey it more closely than English, i.e. most of European ones, have very few debates about how best to teach reading and writing.

The estimates are that about 80% of monosyllabic words are regular from letters to phonemes according to phonics, but this percentage will be much lower when considering all words. As we note in our papers, the mappings between phonemes and letters are even less regular — the linguist David Crystal estimates that only around 50% of the words are predictable. And there is a clear reason for this — spellings are designed around phonology and meaning. This is contrary to the alphabetic principle.

It may be true that it is easier to learn to read in languages with a shallow orthography (i.e., languages that follow the “alphabetic principle”, but the fact of the matter is that English is not such a language. To teach it like it is might be part of the reason why English children are slower. But is also worth noting that it is not so clear that English children are slower to learn to read for meaning. Rather, the evidence is only that English children are slower to learn how to name aloud words. Check out the following paper that shows that slower development in learning to name aloud words is quite different than learning to comprehend text when comparing English to Welsh.

Ellis, N. C., & Hooper, A. M. (2001). Why learning to read is easier in Welsh than in English: Orthographic transparency effects evinced with frequency-matched tests. Applied Psycholinguistics, 22(4), 571-599.

Thanks for your interesting comments!

Jeff

Dear Jeff

I learned English after Lithuanian and Russian and before German, French, Spanish and a bit of Italian. So I learned first hand that learning to read and write English is far more difficult than at least six other languages. But there is plenty of research evidence too, especially a UK study in 1963-4 which compared English literacy acquisition with traditional spelling and the more consistent i.t.a. system – https://literacyproblems.blogspot.com/2018/01/easier-learning-of-reading-and-writing.html

I am absolutely certain that the difference in the speed of Finnish and English literacy acquisition, 3 months v 3 years for reading and 1 year v 10 years for basic writing competence, are entirely due to the exceptional regularity of Finnish spelling and the lack of alphabetic consistency in English https://literacyproblems.blogspot.com/2018/03/spelling-systems-literacy-learning.html Having to spend an exceptionally long time on learning to read and write, which is very similar for all teaching methods, disadvantages Anglophones for the whole of their primary education, and for many pupils at secondary level too.

To me, the obvious solution is to consider improving the consistency of English spelling. Why persist with giving kids a much harder time than need be, mainly because of thoughtless changes to English spelling between the 15th and 18th centuries https://englishspellingproblems.blogspot.com/2012/12/history-of-english-spelling.html? They were not ‘designed around phonology and meaning’. They were either random, ill-intentioned or pompous. Other European countries have shown far more concern for ease of literacy acquisition.

What bothers me most is the wastefulness of English spelling. Apart from more literacy failure and lower overall educational attainment, it robs many other subjects of adequate time-allocations.

Most people could not cope with computers when this required learning DOS rules. Once Windows made it easier, it became accessible to nearly everyone. Making English spelling a bit more sensible, by undoing some of the worst changes inflicted on it http://improvingenglishspelling.blogspot.co.uk, would have the same effect on literacy acquisition.

What dialect of English would you suggest to make regular? The Queen’s English? That would leave a lot of exceptions for Scottish speakers, not to mention the various dialects of English speakers from England, USA, Canada, etc.. For whatever reason, English evolved to represent morphemes in a highly consistent manner, and sacrificed GPC consistency. We can argue whether that is a good outcome or not, but that is what we have. It is not going to change, so I would suggest we teach children that English spellings makes sense when viewed as a morphophonemic system rather than saying that we have an alphabetic system that fails about 50% of the time when trying to spell..

1.What dialect would I make regular?

– Educated English speech is very similar across the world, and the very worst inconsistencies of English spelling are equally troublesome in all accents https://englishspellingproblems.blogspot.com/2019/01/worst-irregularities-of-english-spelling.html

2. I am not suggesting making English spelling as good as Finnish or Korean. – Just a reduction of the irregularities which most hinder literacy progress, like SURPLUS LETTERS for example, which serve no phonemic or semantic function whatsoever but make learning to read much harder than need be, ‘car, care – arE; chav, gave – havE; bed, bead – heAd..’.

To claim that that ‘English evolved to represent morphemes in a highly consistent manner’ is as great an untruth as the claim that English has perfectly teachable relationships between sounds and letters, but which teachers fail to grasp and teach, as made by phonics evangelists.

Neither claim enables readers to cope any better with the phonically variable spellings which keep making them stumble (e.g. and – any, able; on – only, once; fiend – friend; although, through, tough…), and which make learning to read English exceptionally heavily dependent on individual help and are especially bad for children who don’t get much of it at home.

Masha,

Your interest appears set on the idea of reforming the spelling system as the way to address the difficulties some have with learning literacy. You say that the evidence for this is that other languages with shallow orthographies (closer to one-to-one “letter-sound” correspondence) are much easier to learn. Based on that, you argue for altering English spelling to make it shallower.

We happen to disagree profoundly that this is a productive way forward. Linguistics defines orthography as the writing system that evolves to represent the sense and meaning of the language to those who already know and speak the language. Like it or not, English orthography has evolved to represent oral English, and Finnish orthography evolved to represent Finnish. The nature of these oral languages are different, thus the nature of the orthographies are different.

English orthography has evolved to represent morphemes consistently where possible. And certainly the evidence is that it prefers consistent representation of morphemes over consistent representations of phonemes.

You cite words like “only” and “once” as not explainable by morphology or phonology. I agree — these spellings are only understandable through the INTERRELATION of morphology, etymology AND phonology.

There is a rich TEDEd video by Gina Cooke at this link: https://tinyurl.com/onion-fam that reveals the connections in meaning and spelling that make sense of these and related spellings.

SWI is not about adding instruction about morphology and phonology. It is about investigating the interrelation of morphology, etymology and phonology.

We’ve shared our understanding on this topic and we are happy that you have shared your view for the need for spelling reform.

It’s fine that you’ve raised the issue of spelling reform, and your arguments for it, but now I’d like to maintain this comment section to the topic understanding about the orthography we have, and how best to teach it as it is.

So for now, I think the best we can do is to agree to disagree on the way forward.

If you want to continue a discussion on this further, please feel free to email me at . If you do, I will recommend we find a time to video conference to discuss. These concepts are far better discussed in a conversation that emails or comments posted back and forth.

Peter

I agree that we will never agree on this and will not comment on here again.

I have today explained my view at greater length in the blog

https://englishspellingproblems.wordpress.com/2019/04/27/will-they-ever-learn/, but doubt that u will want to read it.

Best wishes

Masha Bell

Hello Harriet,

Thanks for engaging with this work! Let’s consider this issue of what we mean by saying English does or does not have an orthography system that follows the alphabetic principle. My sense is that a general understanding of this phrase the “alphabetic principle” is that the primary (only?) job of the alphabetic letters is to spell the “sounds” (phonemes) of words. By definition, the “alphabetic principle” only addresses conventions for associations between pronunciations and the letters that spell those pronunciations. Please correct me if I am not representing a general sense of that phrase, or your own understanding. But working from that definition, let’s look at the evidence Snow presented:

50% of words in English are directly decodable from their written form

a further 36% violate only one sound–letter rule (usually via a vowel)

10% can be spelt correctly if morphology and etymology are taken into account

So even if I accept these numbers, the addition of morphological and etymological information to bring greater order to spelling is now moving BEYOND the alphabetic principle to describe that order.

So according to these numbers 50% of English spelling strictly follows the conventions of the “alphabetic principle.” It is very hard to see this as evidence that English spelling is essentially driven by the alphabetic principle. And if we allow for what they call one violation of a spelling-sound rule, (one violation of the alphabetic principal per word) we can get to 86%.

That leaves a whole lot of words for learners to memorize.

But more importantly, consider the evidence being used to counter our rejection of the alphabetic principle as a principle on which English orthography operates:

1) Under a strict analysis 50% of spellings violate the alphabetic principle.

2) Under an analysis very that allows for one violation of the alphabetic principle per word, 14% of words violate this principle.

I am aware of no area of scientific inquiry in which we can test a hypothesis about how a complex system works, discover that 14% of the data fails to conform to that hypothesis and then conclude that hypothesis holds because the 14% of the data that remains unexplained must be “exceptions.” And of course that 14% is a number that is deeply biased towards supporting the hypothesis alphabetic principle hypothesis.

We are not supposed to blame data for not following the hypothesis, we are supposed to accept the data that fails to follow our hypothesis is falsifying our hypothesis. Once we do that, we are in a position to look for a better hypothesis to explain how English orthography works. What is interesting in the argument presented, including the morphology and etymology is a way of reducing the amount of un explained data.

Especially with that first 50% number presented as how many words truly follow the alphabetic principle, shouldn’t the recognition that including attention to morphology and phonology reduces the irregularity provoke a new hypothesis that maybe English spelling isn’t a sound representation system, but maybe it is a system that represents the interrelationship of these aspects of language — morphology, etymology and phonology?

But I think there is something else at work. There is an untested hypothesis from many that the morphology and etymology part of orthography is too advanced for those beginning readers. I understand that fear. Given that most people have never seen what that instruction can look like, it is hard to imagine how to even start such instruction.

Snow’s final part of your quote reflects what we are used to seeing in young classrooms:

“And of course, for beginning readers, it makes sense to start with examples that do show this 1:1 correspondence as a “way in”.”

Why can we assume without testing that starting with the decodable ways is the best way in? What if including study of morphologically related families of words from the beginning and investigating the grapheme-phoneme correspondences in that context is more effective? It needs to be clear is that in SWI classrooms, teachers address grapheme-phoneme correspondences explicitly right at the very start of formal instruction. It’s just that it does so with reference to morphology and etymology. Phonics is instruction that reflects the alphabetic principle understanding of English spelling. Instead, since SWI builds on what we know about the interrelation of morphological, etymological and phonological instruction teaches “orthographic phonology”. In SWI we teach not only what are the possible grapheme-phoneme correspondences (which phonics does) it also teaches how can you know which grapheme for a given word by looking at (morphologically and etymologically) related words.

Why do we accept the hypothesis that we must start with letter-sound correspondences without reference to the influence of morphology and etymology? It turns out all the morphological meta-analyses show that the youngest and less able gained the most from including morphological instruction. That is not the result that would be predicted if including morphology from the start reduced learning outcomes. Goodwin and Ahn pointed out that in their two meta-analyses of morphological instruction (2010, 2013) the outcome with the greatest effect sizes were for phonological awareness; morphological awareness came in second! As they argued, this is evidence for a synergistic relationship between morphological instruction and phonological learning. Again, this does not comport with the view that the best place to start is teaching about phonological aspects of spelling without reference to morphology or etymology (phonics instruction) and then add morphology and perhaps etymology later. The only study I know of that compared a phonics treatment and an SWI treatment was with 5-7 year olds by Devonshire, Morris and Fluck (2013). They compared what classifies as an SWI condition to a phonics condition and found significant effects on standardized measures of reading and spelling. (See their paper here: https://tinyurl.com/devonshire-Morris-Fluck-2013).

There is not enough research on this question, but what seems to be a common state of affairs is a rejection of any challenge to the hypothesis of “the alphabetic principle”. And yet we know it fails to represent how our system works compared to linguistic descriptions. We also know that we have a large number of students who struggle in the context of typical instruction. We also have evidence that including aspects of the language beyond isolated phonological cues from the beginning brings its greatest benefits to the younger and less abled.

All of this provides reason to test the hypothesis that not only adding morphology to phonics lessons, but actually explicitly teaching the interrelation of morphology, etymology and phonology from the beginning might provide significant benefits to learning. That’s the way the evidence points now, but we do need more evidence. But to get funding for such studies and to get such studies published, we do need a scientific community that is open to questioning something has long been seen as essential literacy instruction — the alphabetic principle.

Another blockage is simply that so few have any sense of what SWI instruction could even look like in the early years. Here are just a couple examples as a reference.

At my YouTube page

https://www.youtube.com/user/WordWorksKingston

the first video is of me teaching a young class about the spelling of by looking at related words with a matrix and word sums.

My colleague, Rebecca Loveless has a great website with many illustrations of early SWI instruction that addresses the interrelationship of morphology, etymology and phonology. Explore here: http://rebeccaloveless.com

I hope this is helpful. I’m eager for further critical analysis from you about anything here or in Jeff’s posts!

People still argue about how regular or irregular English spelling is, instead of simply taking a look at the facts: Among the 7,000 most used English words (i.e. ones that the majority of 16-yr-olds are like to be fairly familiar with) 4,219 contain irregular spellings like ‘speak, seek, shriek’ and 2,039 contain graphemes with variable pronunciations, like ‘on, only, once, other’. These facts are available for verification on my blog http://englishspellingproblems.blogspot.co.uk

I have written books about this too. Teaching children to read and write English is difficult simply because it is not truly alphabetic, in the sense of representing speech sounds in a regular manner. It is a mixture of alphabetic and un-alphabetic. That is why no teaching method will ever work equally well with all children.

An awareness of morphology can help a little, but the main difficulty in learning to read is caused by spellings with variable pronunciations.

Dear Masha, the main reason why spellings have variable pronunciations is that spellings prioritise the consistent spellings of morphemes over phonemes. The spellings of morphemes is highly consistent — on what basis do you claim that morphological awareness can only help a little?

Jeff

The spellings of English prefixes and suffixes are fairly rule-governed. But in the stems of words, they are very unreliable. U even get nonsense like ‘speak – speech’, ‘seize – siege’ and ‘four, fourteen – forty’. For young children especially, when they are still learning the language itself as well as grammar, alphabetic inconsistencies like ‘dream – dreamt’ and ‘to read – read yesterday’ make life very much harder than ‘sleep – slept’, ‘keep – kept’.

English spelling is not completely chaotic, but as an alphabetic system, it has five major defects which make learning to read and write exceptionally laborious and time-consuming:

https://improvingenglishspelling.blogspot.com/2019/03/main-defects-of-english-spelling.html

Hello Masha,

You write, “Teaching children to read and write English is difficult simply because it is not truly alphabetic, in the sense of representing speech sounds in a regular manner.” What Jeff and I are arguing is that teaching to read and write in English is particularly difficult when it is taught as though it follows an “alphabetic principle”. What we are suggesting is that the default instructional principle should be that instruction provides a valid representation of the content of instruction. Literacy instruction that leaves the impression that spelling is an alphabetic system in which the primary job of letters is to represent sounds, then we have failed at that basic premise. The primary job of an orthography is to represent the sense and meaning of words to those who already know and speak the language. It is on this principle that SWI is based. And that means it teaches about the interrelation of morphology, etymology and phonology from the beginning.

Indeed there are many words in English like “strong verbs” where a default way of marking the past tense with an suffix is not used (e.g. read/read, sleep/slept, know/knew). But these words are rich to study. One thing we can discover about “strong verbs” is that they are very old. And they are called “strong” because as other words became regularized to patterns like adding the past tense suffix “-ed” some commonly used words (at the time) were “strong” and resisted that change. We can collect words that do not use the standard grammatical suffixes and then study those to see what we can learn. In my experience, this story about “strong” and “weak” verbs is one that struggling students appreciate. There is a story to these spellings that can be understood. And then some, like the past “read” and present “read” have extra bonuses. Of course the past tense “read” is homophonic with the colour “red” and the present tense “read” is homophonic with the part of a plant called a “reed” that is also used in reed instruments. So with that little set of words, we can see that — given the oral language does not have a standard past tense suffix, instead it used a stem-vowel shift to mark that grammatical roll, it makes sense the we use the consistent spelling with the “ea” digraph that can link these related words, while distinguishing the spelling from the homophones “red” and “reed”.

Some may think that, this is a lot of work for a couple words. But the point is not just these words — its about using these words to build an orthographic understanding that can then be used to take on other surprising spellings.

Struggling students demonstrate they do not flourish with memorization of words they are told are “irregular”.

Whatever changes we make to literacy instruction, I can’t believe that misrepresenting how the spelling system works is a wise way forward for any learner. I can’t see harm in continually refining and testing instruction that reflects how this meaning-representation system works.

Hi Harriett, thanks for your nice comments. Regarding whether English is analphabetic system, the point is whether letters are only designed to represent phonemes (like in shallow orthographies) or whether letters are designed around phonemes and meaning. There is no question that English spellings are organized around both, making it a morphophonological system. It is not only that spellings are influenced by meaning, the English spelling system prioritizes the consistent spelling of morphemes over phonemes, which explains why there are so many “irregular” words. The fact that there is a in is a feature rather than a bug of the system – in order to spell consistently in and , etc. The prioritization of meaning is also reflected in the fact that most homophones are spelt differently – just the opposite as you would expect if English followed the alphabetic principle.

Thanks Jeff and Pete for another fascinating article and for the Dehaene citation, which I also found very interesting. As I’ve mentioned before, I think about this debate weekly as I work with my 45 struggling readers. I’m wondering what you think of these comments by Pamela Snow:

I am however not in agreement with the proposition that “English is not an alphabetic language”. I think everyone needs to be careful about over-generalisations in this space. It is not like Italian or Spanish, but neither is it random. I have referred in previous blogposts to the work of Louisa Moats (2010) who draws on the earlier work of Hanna et al (1969) to point out that some 50% of words in English are directly decodable from their written form and a further 36% violate only one sound–letter rule (usually via a vowel), 10% can be spelt correctly if morphology and etymology are taken into account and fewer than 4% are truly irregular. And of course, for beginning readers, it makes sense to start with examples that do show this 1:1 correspondence as a “way in”.