Go to | Basic Research

Go to | Applied Research

Literacy Instruction: Phonics is the most common form of early reading instruction in English speaking countries. Indeed, it is legally required in UK state schools. However, there are good reasons to explore alternative approaches, and I am interested in considering an alternative approach called Structured Word Inquiry.

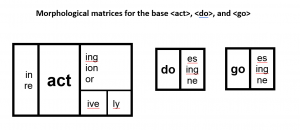

The first reason to question phonics is that it is built on a false understanding of how the writing system works. In contrast to the common view that the English spelling system is a poorly designed phonological system (full of exception words), it is fact a morphophonemic system in which spellings have evolved to represent sound (phonemes), meaning (morphemes), and history (etymology) in an orderly way. Indeed, English spelling favors the consistent spelling of morphemes (meaning bearing elements) over the consistent spelling of phonemes. To illustrate, consider the morphological families associated with the bases <act>, <do>, and <go> in the Figure below.

The spellings of the bases are consistent across all members of the morphological families despite pronunciation shifts (e.g., acting vs. action; do vs. does; go vs. gone). Or consider the consistent spelling of the <-ed> suffix in <jumped>, <played>, and <painted> despite the fact that <-ed> is associated with the pronunciations /t/, /d/ and /ɪd/, respectively. Note, the letter sequence <ed> within a base (e.g., <bed>, <red>, <Ted>, <wed>) has yet another pronunciation, /ɛd /, that never occurs for the <-ed> suffix. These are not idiosyncratic examples: The consistent spelling of morphemes over phonemes is a fundamental organizing principle of the English spelling system. In order to spell morphemes in a consistent manner it is necessary to have inconsistent (or perhaps a better term is ‘flexible’) letter-sound correspondences. For a more detailed tutorial in the logic of the English spelling system see Bowers and Bowers (2017).

It is a striking fact that few teachers or researchers understand that English spelling system makes sense. In contrast to the common claim that English spelling system is crazy and full of sight words (<action>, <does>, <gone>, <have>, <sign>, etc., etc., etc.; ~20% of all words are classified as “irregular” for naming and ~50% of words have unpredictable spellings), Chomsky calls the English spelling system “optimal”. Whether or not it is optimal, it is a very different system than is assumed by proponents of phonics that assumes that English spelling system is highly flawed and largely phonological.

The second reason is that phonics instruction is not working for too many children. There are many studies that show phonics is better than whole language, but that is no reason to assume that phonics can’t be improved on. In fact, the evidence for phonics is surprisingly weak and mixed, as briefly reviewed by Bowers and Bowers (2017). For a more detailed review that also highlights the limited efficacy of phonics see: Suggate, S. P. (2016). A meta-analysis of the long-term effects of phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, and reading comprehension interventions. Journal of learning disabilities, 49(1), 77-96.

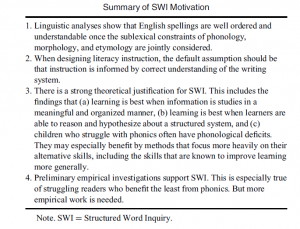

What is the alternative? As we detail in Bowers and Bowers (2017), the false characterization of the writing system often restricts the types of instruction that are considered. We would suggest that instruction should be organized around the fact that the English spelling system is morphophonemic. Structured Word Inquiry (SWI) is an alternative approach based on the following set of assumptions (taken from Bowers and Bowers, 2017).

With regards to point 4, there is growing evidence that morphological interventions are useful, especially for young and struggling children, and some initial studies showing the promise of SWI, including children as young as 5-7. To date few studies have directly compared phonics with meaning-based forms of instruction that emphasize the sub-lexical structure of words. Accordingly, the common claim that that initial instruction should focus on grapheme-phoneme correspondences to the exclusion of meaning-based approaches is unwarranted. Importantly, there is a reason why so little consideration has been given to comparing these approaches, namely, the widespread assumption that the main function of letters is to represent sounds precludes the consideration of SWI and other approaches that target the meaningful regularities of English spellings.

This has all proved very controversial. Have a look at my blogposts for more detail.

Educational Neuroscience: There is growing interest in the claim that neuroscience can improve education. New journals (Mind, Brain, and Education; Trends in Neuroscience and Education), research centers (e.g., Cambridge Centre for Neuroscience in Education), as well as research degrees and conferences have been established. Many recent high-profile papers in Nature, Nature Neuroscience, Nature Reviews Neuroscience, Science, and Neuron all attest to the promise of this approach.

There is growing interest in the claim that neuroscience can improve education. New journals (Mind, Brain, and Education; Trends in Neuroscience and Education), research centers (e.g., Cambridge Centre for Neuroscience in Education), as well as research degrees and conferences have been established. Many recent high-profile papers in Nature, Nature Neuroscience, Nature Reviews Neuroscience, Science, and Neuron all attest to the promise of this approach.

By contrast, I argue that neuroscience, or ‘educational neuroscience’ has little to contribute. Indeed, despite all the excitement, there is not a single example of neuroscience improving instruction in the classroom. Note, my claim is not that science is irrelevant to education, but rather, the study of the brain is irrelevant. When assessing the efficacy of instruction, the only question relevant to the child and teacher is whether the child learns, as reflected in behavior. Accordingly, education researchers should look to psychology rather than neuroscience.

I was recently involved in a debate on this subject, and I see no reason to change my mind after our exchange. I noted: “Following this exchange there are still no examples of [Educational Neuroscience] EN providing new insights to teaching in the classroom, there are still no examples of EN providing new insights to remedial instructions for individuals, and as I detail here, there is no evidence that EN is useful for the diagnosis of learning difficulties”.

Bowers, J. S. (2016). The Practical and principled problems with educational neuroscience. Psychological Review, 123, 600-612.

Bowers, J. S. (2016). Psychology, not educational neuroscience, is the way forward for improving educational outcomes for all children: Reply to Gabrieli. Psychological Review, 123, 628-635.

Bowers, J.S., & Bowers, P.N. (2017). Beyond Phonics The Case for Teaching Children the Logic of the English Spelling System. Educational Psychologist, 52, 124–141. 2017