Responding to Buckingham’s post entitled: “The grass is not greener on Jeffrey Bowers’ side of the fence: Systematic phonics belongs in evidence-based reading programs”

Buckingham wrote a long response (download here) to my recent paper entitled “Reconsidering the evidence that systematic phonics is more effective than alternative methods of reading instruction” (that you can download here). I previously responded to Buckingham post in a series of 5 separate posts, and here I’ve combined them into one long response in return. I’ve edited them slightly to better link the posts as well as made some minor changes. Enjoy!

I am pleased that Buckingham has provided a detailed response to my article, but almost every point she makes regarding my review of the evidence is either factually incorrect or a mischaracterization. There is nothing in her post that challenges the conclusions I’ve drawn. I first address her points regarding the meta-analyses, then consider her responses to the reading results in England post 2007 when systematic synthetic phonics was legally mandated in state schools, and then make the general point that politics in “the science of reading” is biasing what gets published.

Buckingham’s first response concerns the National Reading Panel (NRP) meta-analysis. Her summary of my critique of is as follows:

“In his summary of the National Reading Panel (NRP) analysis, Bowers argues that the effect sizes are not large and do not justify the NRP’s conclusions that systematic phonics should be taught in schools. However, the effect sizes quoted by Bowers are moderate to high, especially for synthetic phonics in particular, and are certainly stronger than the evidence found for any other method, including whole language”.

This is wrong in multiple many ways. First, it a gross mischaracterization of my summary, which I provide in the paper itself:

“In sum, rather than the strong conclusions emphasized the executive summary of the NRP (2000) and the abstract of Ehri et al. (2001), the appropriate conclusion from this meta-analysis should be something like this:

Systematic phonics provides a small short-term benefit to spelling, reading text, and comprehension, with no evidence that these effects persist following a delay of 4– 12 months (the effects were not reported nor assessed). It is unclear whether there is an advantage of introducing phonics early, and there are no short- or long-term benefit for majority of struggling readers above grade 1 (children with below average intelligence). Systematic phonics did provide a moderate short-term benefit to regular word and pseudoword naming, with overall benefits significant but reduced by a third following 4–12 months.”

And as a point of fact, Buckingham’s claim that “the effect sizes quoted by Bowers are moderate to high, especially for synthetic phonics in particular” is straightforwardly contradicted by the following point from my paper:

“And although the NRP is often taken to support the efficacy of synthetic systematic phonics (the version of phonics legally mandated in the UK), the NRP meta-analysis only included four studies relevant for this comparison (of 12 studies that compared systematic phonics with whole language, only four assessed synthetic phonics). The effect sizes in order of magnitude were d = 0.91 and d = 0.12 in two studies that assessed grade 1 and 2 students, respectively (Foorman et al. 1998); d = 0.07 in a study that asses grade 1 students (Traweek & Berninger, 1997); and d = − 0.47 in a study carried out on grade 2 students (Wilson & Norman, 1998).”

It is worth highlighting this point. The NPR has no doubt been cited 100s of times in support of the claim that synthetic phonics is more effective than whole language. But if you look carefully, this is the basis for this claim.

Also, according to the NRP itself, there is no statistical evidence that synthetic phonics is more effective than other forms of systematic phonics:

“Are some types of phonics instruction more effective than others? Are some specific phonics programs more effective than others? Three types of phonics programs were compared in the analysis: (1) synthetic phonics programs that emphasized teaching students to convert letters (graphemes) into sounds (phonemes) and then to blend the sounds to form recognizable words; (2) larger-unit phonics programs that emphasized the analysis and blending of larger subparts of words (i.e., onsets, rimes, phonograms, spelling patterns) as well as phonemes; and (3) miscellaneous phonics programs that taught phonics systematically but did this in other ways not covered by the synthetic or larger-unit categories or were unclear about the nature of the approach. The analysis showed that effect sizes for the three categories of programs were all significantly greater than zero and did not differ statistically from each other. The effect size for synthetic programs was d = 0.45; for larger-unit programs, d = 0.34; and for miscellaneous programs, d = 0.27”

Also, note these effect sizes. Cohen suggested that d=0.2 be considered a ‘small’ effect size, 0.5 represents a ‘medium’ effect size and 0.8 a ‘large’ effect size. So unclear why Buckingham writes: “the effect sizes quoted by Bowers are moderate to high, especially for synthetic phonics in particular, and are certainly stronger than the evidence found for any other method, including whole language”. Indeed, as noted above, the NRP only had 4 studies that compared synthetic phonics to whole language.

Buckingham next criticizes my review of Camilli et al. and argues that these analyses provide further support for systematic phonics. Here are the key passages from her response:

“Bowers presents the findings of two re-analyses of the studies included in the NRP by Camilli, Vargas and Yurecko (2003) and Camilli, Wolfe and Smith (2006) that are alleged to dispute the NRP’s conclusions. Yet after some substantial re-engineering of the data, Camilli, Vargas and Yurecko (2003) still found that the effect of systematic over non-systematic phonics instruction was significant.”

And…

“Camilli, Wolfe and Smith (2006) manoeuvered the data even more, creating a multi-level model that included language-based activities as a moderating variable. It reinforced the finding that systematic phonics was superior to no phonics but reduced the simple effect of systematic phonics over non-systematic phonics, which Bowers incorrectly interprets to mean that “Camilli et al (2006) failed to show an advantage of systematic over unsystematic phonics” (p. 9).

Buckingham concludes: “Overall, far from presenting a challenge to systematic phonics, the findings of Camilli et al. can be described as supporting the conclusion that some phonics instruction is better than no phonics instruction, and the more systematic the phonics instruction is, the better. The best case scenario is systematic phonics instruction paired with high quality language activities.”

The first thing to note is that Buckingham seems to think that Camilli et al are up to no good, writing: “Yet after some substantial re-engineering of the data” and “Camilli, Wolfe and Smith (2006) manoeuvered the data even more”…. This seems to relate to Greg Ashman’s criticism of Camilli et al. in his earlier critique of my work that is nicely summarized in a recent tweet by him:

“The fundamental flaw is it’s all post hoc. Bowers is slicing and dicing the meta-analyses to suit his hypothesis. He relies heavily on Camilli who also slice and dice the results. You can prove pretty much anything that way.”

The first thing to note is that there is nothing arbitrary or post-hoc about the Camilli et al.’s analyses. As noted by the authors of the NRP, almost all forms of instruction in the USA included some degree of phonics, with systematic phonics less common. So, when claiming the science of reading supports a change to systematic phonics, the relevant question is whether systematic phonics is better than some phonics. Because the NRP did not test this hypothesis, Camilli et al. carried out new meta-analyses to address this question. There is absolutely nothing post-hoc about asking this reasonable question. The authors also wanted to distinguish the impact of systematic phonics from one-one tutoring and language-based activities more generally. Again, nothing post-hoc about asking this, let alone “substantial re-engineering of the data”. They carried out new meta-analyses to ask a new set of reasonable questions.

But what about the results? Do they provide further support for systematic phonics? In first analysis Camilli et al found the benefit of systematic phonics was reduced to .24 (from .41), but nevertheless, the effect was still significant. Great news for systematic phonics! Well, no. What one should note is that this overall effect that combines the results from decoding of nonwords, regular words, etc. Based on these results there is no reason to think that systematic phonics improved any reading outcome other than decoding for the short-term. And furthermore, in a subsequent analysis of this same dataset (with a more careful assessment additional variables and improved statistics), Camilli et al. (2006) found that there was no longer any significant main effect of systematic phonics compared to unsystematic phonics. Instead, according to the Camilli et al. (2003, 2006), the strongest effect in the studies included in the NRP came from one-on-one tutoring.

For some reason Buckingham claims I am incorrect in writing: “Camilli et al (2006) failed to show an advantage of systematic over unsystematic phonics”. But that is exactly what they found. And even if the nonsignificant d = .12 is taken to support systematic phonics over non-systematic phonics, the effects will mostly be driven by short-term measures of decoding, with even weaker effect sizes for all other measures of reading, and weaker effects still with children with reading difficulties (remember, Camilli et al. are working with largely the same dataset as the NRP). Indeed, as we will see later, subsequent meta-analyses highlight how systematics phonics does not have long-lasting effects on reading outcomes, and that children with reading difficulties do indeed benefit the least.

To summarize thus far, the NRP provides weak evidence at best that systematic phonics improves reading outcomes, little or no evidence for synthetic phonics is better than whole language, and the main design of the NRP did not even test they hypothesis that systematic phonics is better than common alternatives in schools. There is no basis whatsoever for Buckingham’s claim that the effect sizes in the NRP “are moderate to high, especially for synthetic phonics in particular”. When meta-analyses were designed to test whether systematic phonics is better than common alternatives that include some (nonsystematic) phonics, the effects are dramatically reduced, and indeed, in one analysis, the overall analysis is not even significant. There are no good scientific grounds to argue that the NRP or the Camilli et al. meta-analyses provide good support for systematic phonics.

The next meta-analysis by Torgerson et al. (2006) further undermines the conclusions that can be drawn from the NRP. What the authors note is that few of the studies included in the NRP were RCT studies, and the quality of the studies is problematic. Here is a passage from this meta-analysis that specifically focused on 14 RCT studies that exist (including one unpublished study):

“None of the 14 included trials reported method of random allocation or sample size justification, and only two reported blinded assessment of outcome. Nine of the 14 trials used intention to teach (ITT) analysis. These are all limitations on the quality of the evidence. The main meta-analysis included only 12 relatively small individually randomised controlled trials, with the largest trial having 121 participants and the smallest only 12 (across intervention and control groups in both cases). Although all these trials used random allocation to create comparison groups and therefore the most appropriate design for investigating the question of relative effectiveness of different methods for delivering reading support or instruction, there were rather few trials, all relatively small, and of varying methodological quality. This means that the quality of evidence in the main analysis was judged to be “moderate” for reading accuracy outcomes. For comprehension and spelling outcomes the quality of evidence was judged to be “weak”.

So not a great basis for making strong conclusions.

But what about the results? Jennifer Buckingham writes: “After limiting the included studies to RCTs, Torgerson, Brooks and Hall (2006) found moderate to high effect sizes for systematic phonics on word reading (0.27 to 0.38) and comprehension (0.24 to 0.35), depending on whether fixed or random effects models were used. The word reading effect was statistically significant. After removing one study with a particularly high effect size, the overall result was reduced for word reading accuracy but still of moderate size and still significant.”

Again, the claim that the effects were moderate to high is at odds with the effect sizes, and this summary does not capture the fact that the comprehension effect was not significant, nor was spelling (d = 0.09). And as noted by Torgerson et al. *themselves*, after removing a flawed study with an absurd effect size of 2.69, the spelling effect just reaching significance one analysis (p = 0.03) and nonsignificant on another (p = 0.09). For Buckingham to summarize this as a significant and moderate effect is misleading (never mind the replication crisis that has highlighted how insecure a p < .05 effect is).

Torgerson et al. also reported evidence of publication bias in support of systematic phonics. This bias will have inflated the results from previous meta-analyses, and the fact that the authors identified one additional unpublished study does not eliminate this worry. More importantly, the design of the study did not even compare systematic phonics compared to some phonics that is common in school settings. If this comparison was made, the effect sizes would be reduced even further. This means that the following claim by Torgerson et al.’s regarding whole language is unjustified. “Systematic phonics instruction within a broad literacy curriculum appears to have a greater effect on childrens progress in reading than whole language or whole word approaches”.

In sum, Torgerson et al. assessed the efficacy of systematic phonics on spelling, comprehension, and word reading accuracy. The first two effects were not significant, and the word reading accuracy results according to their own analysis was borderline (significant on one test, not on another). Torgerson et al. did not even test whether systematic phonics was more effective than standard alternative methods that include some phonics. On top of this, as noted by Torgerson et al., the quality of the studies in their meta-analysis was mixed. It is hard to reconcile these facts with Buckingham’s characterization of the findings. As we will see, all subsequent meta-analyses are even more problematic for the claim that the science of reading supports systematic phonics compared to common alternatives.

The next meta-analysis was carried out by McArthur et al. (2012). Buckingham does make one valid point, namely, I missed the update meta-analysis from 2018, but let’s consider whether indeed I have mischaracterized the results from 2012 paper as claimed. I noted that the McArthur et al. reported significant effects of word reading accuracy and nonword reading accuracy, whereas no significant effects were obtained in word reading fluency, reading comprehension, spelling, and nonword reading fluency. But I also argued that the significant word reading accuracy results depended on two studies that should be excluded, and when the studies are removed, the word reading accuracy results are no longer significant (leaving only nonword reading accuracy significant). Buckingham commented:

“Bowers argues that the high results for word reading accuracy were due to two studies — Levy and Lysynchuck (1997) and Levy, Bourassa and Horn (1999) — and that these studies should be excluded because they were one-to-one interventions. However, all of the studies in this meta-analysis were small group or one-to-one interventions, so there is no good reason to exclude these two particular studies just because the interventions were found to be particularly effective. Nonetheless, in Bowers’ summary he unilaterally decides to remove the Levy et al. studies and comes to the spurious and erroneous conclusion that the McArthur et al. (2012) meta-analysis found “no evidence” that systematic phonics instruction was effective.”

This summary is a complete misrepresentation of my motivation for removing the studies. This is what I wrote: “One notable feature of the word reading accuracy results is that they were largely driven by two studies (Levy and Lysynchuk 1997; Levy et al. 1999) with effect sizes of d = 1.12 and d = 1.80, respectively. The remaining eight studies that assessed reading word accuracy reported a mean effect size of 0.16 (see Appendix 1.1, page 63). This is problematic given that the children in the Levy studies were trained on one set of words, and then, reading accuracy was assessed on another set of words that shared either onsets or rhymes with the trained items (e.g., a child might have been trained on the word beak and later be tested on the word peak; the stimuli were not presented in either paper). Accordingly, the large benefits observed in the phonics conditions compared with a nontrained control group only shows that training generalized to highly similar words rather than word reading accuracy more generally (the claim of the meta-analysis). In addition, both Levy et al. studies taught systematic phonics using one-on-one tutoring. Although McArthur et al. reported that group size did not have an overall impact on performance, one-on-one training studies with a tutor showed an average effect size of d = 0.93 (over three studies). Accordingly, the large effect size for word reading accuracy may be more the product of one-on-one training with a tutor rather than any benefits of phonics per se, consistent with the findings of Camilli et al. (2003).”

That is, my main motivation for removing the studies is that word reading accuracy was assessed on words that were very similar to the study words. I quite like a tweet by Stephanie Ruston who wrote “I almost fell out of my chair when I read that mischaracterization of Bowers’ discussion of the Levy et al. studies. I mean, people can easily search through his paper to read that section for themselves. It’s unfortunate that many will not do so before forming a conclusion.”

It is perhaps worth detailing a bit more what was done in these studies to see if my reasoning is justified (I would not want to be called post-hoc). The children in the Levy and Lysynchuk (1997) were taught 32 words composed of 8 onsets (fi, ca, bi, pa, wi, ma, pi, ra) and 8 rimes, (it, ig, in, ill, up, an, ash, at). They studied these 32 words were taught one-on-one with a tutor once a day for 15 days or until the child could pronounce all 32 words correctly on 2 successive days. At test, children read 48 new words and 48 nonwords composed of these onsets and rimes. For example, children would be taught can, pan, ban that all share the rime an, and then tested on fan. The authors found that these children were more accurate at reading these words and nonwords than another group of children who were given no instruction on these specific onsets and rimes (indeed, they were not given any extra reading instruction at). It was fine for Levy et al. to compare the efficacy of different ways of studying these 32 words (they found an “onset” phonics method was better than a “phoneme” method), but to use these findings in a meta-analysis that claims that systematic phonics improves word reading accuracy in general is inappropriate. Yes, if an instructor knows the test words and then trains children for 15 days one-one-one on a set of words as similar as possible to the test words, then these children do better than children who get no instruction at all. Levy et al. (1999) carried out a similar study, and for this same reason, the large effects on word reading accuracy should be excluded here as well. Indeed, the nonword reading accuracy results from both studies should be excluded as well.

Let’s move on to the next meta-analysis by Galuschka et al. who found the overall effect sizes observed for phonics (g′ = 0.32) was similar to the outcomes with phonemic awareness instruction (g′ = 0.28), reading fluency training (g′ = 0.30), auditory training (g′ = 0.39), and color overlays (g′ = 0.32), with only reading comprehension training (g′ = 0.18) and medical treatment (g′=0.12) producing numerically reduced effects. Despite this, the authors wrote:“This finding is consistent with those reported in previous meta-analyses… At the current state of knowledge, it is adequate to conclude that the systematic instruction of letter- sound correspondences and decoding strategies, and the application of these skills in reading and writing activities, is the *most* effective method for improving literacy skills of children and adolescents with reading disabilities” [I’ve added the *].

As a basic matter of statistics, the claim that phonics is *most* effective requires an interaction, with phonics significantly more effective than alternative methods. They did not test for an interaction, and a look at the effects sizes shows there is no interaction. Nevertheless, Buckingham writes “Galuschka, Ise, Krick and Schulte-Korne (2014) have not overstated the case for systematic phonics interventions. Based on statistical significance, they explicitly say that “At the current state of knowledge”, their conclusion about the relative effectiveness of systematic phonics instruction is sound. This simply means that, at this point in time, we can have more confidence in this finding than in the effect sizes found for the other treatment conditions.”

I’m not sure how the “current state of knowledge” helps justify Galuschka et al.’s conclusion, nor am I’m not sure how the rewording of the conclusions justifies what the authors actually wrote. Here is a fair characterization of what was found: Similar effect sizes were obtained across multiple different forms of instruction, with only phonics significant. However, there was no evidence that phonics was more effective than other methods.

Buckingham is also critical of my claim that there was evidence for publication bias that inflated the phonics results, writing:

“Bowers disputes this conclusion, once again raising the spectre of publication bias with little real reason to do so. The speculation about publication bias inflating the results is very unpersuasive. There are many people who would be delighted to publish studies showing a null result of phonics instruction so the idea that there are a lot of undiscovered, unpublished studies out there showing null results is difficult to believe”.

I have to confess I had a wry smile when Buckingham wrote it is “difficult to believe” in publication bias in the domain of reading instruction (I cannot exaggerate how difficult it was to publish this paper or my previous papers on SWI – see the last section of this article), but in any case, the statement is misleading as it was Galuschka et al. *themselves* that raised this concern and found evidence for publication bias, writing:

“A funnel plot was used to explore the presence of publication bias. The shape of the funnel plot displayed asymmetry with a gap on the left of the graph. Using Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill [44] the extent of publication bias was assessed and an unbiased effect size was estimated. This procedure trimmed 10 studies into the plot and led to an estimated unbiased effect size of g’ = 0.198 (95% CI [0.039, 0.357]) (see Figures 4 and 5, Table 4).”

And once again, this meta-analysis did not even test the hypothesis that systematic phonics is more effective than standard alternative methods that include some degree of phonics. So again, Buckingham has made a number of mischaracterizations of the original study and my work.

With regards to the Suggate (2010) meta-analysis, I wrote: “The critical novel finding, however, was that there was a significant interaction between method of instruction and age of child, such that phonics was most useful in kindergarten for reading measures, but alternative interventions were more effective for older children”. I challenged this conclusion noting that the advantage of early phonics was very small (d estimated to .1) and the study that showed the largest benefit of early phonics was carried out in Hebrew (a shallow orthography where GPCs are highly regular). This obviously weakens the claim that early systematic phonics is particularly important in learning to read English with less regular GPCs.

Buckingham does not mention any of this, and simply concludes. “There is no challenge to the importance of phonics, or the impact of systematic phonics instruction, in these findings.” I would be interested to know whether Buckingham thinks it is fine to use studies from non-English languages to make conclusions regarding English, especially given the effect of this Hebrew study as well as the fact overall the effects were reduced in English compared to other language, as summarized in my paper.

The Suggate (2016) study was the first to systematically assess the long-term impacts of various forms of reading interventions. This is from the abstract: “Much is known about short-term—but very little about the long-term—effects of reading interventions. To rectify this, a detailed analysis of follow-up effects as a function of intervention, sample, and methodological variables was conducted. A total of 71 intervention-control groups were selected (N = 8,161 at posttest) from studies reporting posttest and follow- up data (M = 11.17 months) for previously established reading interventions. The posttest effect sizes indicated effects (dw = 0.37) that decreased to follow-up (dw = 0.22). Overall, comprehension and phonemic awareness interventions showed good maintenance of effect that transferred to nontargeted skills, whereas phonics and fluency interventions, and those for preschool and kindergarten children, tended not to.”

Buckingham simply dismisses the finding that systematic phonics had the smallest long-term effects of all forms of instruction writing: “The lower long-term effects of phonics interventions can be explained by the constrained nature of phonics. Once children have mastered decoding, other aspects of reading instruction become stronger variables in their reading ability”.

I don’t understand how Buckingham can just brush aside a recent meta-analysis that considers all studies that have assessed the long-term effects of systematic phonics. It seems we are getting to the stage where the benefits of systematic phonics are unfalsifiable, with null effects explained away and the conclusion that the science of reading supports systematic phonics unaffected. We will see much more of this when Buckingham considers that reading results in England post 2007. Let me quote from an email from Suggate (the author of the last two meta-analyses) who wrote me after reading my review article (he is happy for me to post this):

“I just came across your paper, hot off the press, on the effectiveness of systematic phonics instruction, which I have read with great interest…

If I may be so upfront, I think that the strongest argument from my meta-analyses in support of your position is to be found in the long-term (still only 11 months) data, namely in the poor performance of the phonics interventions at follow-up (see Table 3 of my 2016 meta-analysis) – these had basically zero effect, except for spelling. So why make such a big deal of phonics when it doesn’t produce lasting effects and doesn’t transfer to other reading skills?”

Finally, Buckingham dismisses my reviews of the other meta-analyses (and review) and writes:

“Part of the problem with this premise is that unsystematic phonics is nebulous and undefined. It involves matters of degree – an absolute example of no phonics would be difficult to find. According to Bowers himself, whole language methods can contain unsystematic phonics. This is arguably more accurately described as balanced literacy; the boundaries are blurry. Given this difficulty of defining what is unsystematic phonics and what is whole language (with or without systematic phonics) and what is balanced literacy, it seems reasonable and practical to do what almost all studies and meta-analyses have done – compare systematic phonics instruction with the absence of systematic phonics instruction.”

The problem with this is that the NRP design specifically compared systematic phonics to a control condition that combined nonsystematic phonics or no phonics. Here is a quote from NRP: “The research literature was searched to identify experiments that compared the reading performance of children who had received systematic phonics instruction to the performance of children given nonsystematic phonics or no phonics instruction”. And here is the conclusion from the NRP: “Findings provided solid support for the conclusion that systematic phonics instruction makes a bigger contribution to children’s growth in reading than alternative programs providing unsystematic or no phonics instruction.”

It is also the case that when Camilli et al reviewed the literature they found interventions that had systematic phonics, nonsystematic phonics, and no phonics. Most subsequent meta-analyses adopted the same criterion of the NRP, comparing systematic phonics to a control condition that had nonsystematic phonics or no phonics. One exception was McArthur et al. (2012) who compared systematic phonics to no instruction. So Buckingham’s characterization of the research and the meta-analyses is again incorrect.

I do agree with Buckingham that there are few examples of instruction in the classroom that include no phonics. And that is exactly why Camilli et al. made the important point that the design of the NRP (and most subsequent meta-analyses) is inappropriate for assessing the importance of systematic phonics compared to standard classroom practice. The fact that there is little or no evidence for systematic phonics even in the face of a control condition that includes no phonics only serves to undermine the evidence for systematic phonics further.

As I wrote in my summary of the meta-analyses: “There can be few areas in psychology in which the research community so consistently reaches a conclusion that is so at odds with available evidence.” I see no reason to change this conclusion based on Buckingham’s analyses of the meta-analyses.

What about Buckingham’s response to the reading results in England since introducing systematic synthetic phonics in 2007? She first considers a paper by Machin, McNally and Viarengo (2018) that assessed the impact of the early roll out of synthetic systematic phonics (SSP) on standard attainment test (SAT) reading results in England. They tested two cohorts of children (what they called the EDRp and CLLP cohorts) and failed to obtain overall long-term effects of SSP in either cohort (consistent with the meta-analysis of Suggate, 2016 that failed to obtain long-term effects of phonics). However, when they broke down both samples into multiple subgroups, they found that the non-native speakers (.068) and economically disadvantaged children (.062) in the CLLD cohort did show significant gains on the key stage 2 test (age 11), whereas these same subgroups in the EDRp cohort did not show significant benefits. Indeed, for the ERDp sample, there was a tendency for more economically advantaged native English children to read more poorly in the key stage 2 test (−0.061), p<0.1 Nevertheless the authors concluded in the abstract: “While strong initial effects tend to fade out on average, they persist for those with children with a higher initial propensity to struggle with reading. As a result, this program helped narrow the gap between disadvantaged pupils and other groups”.

Given the significant long-term effects depend on an unmotivated breakdown of subgroups (2 out of 8 conditions showing significant positive effects at p < .05, and another group showing a strong tendency to do worse, p < .1), you might expect Buckingham to criticize this conclusion as post-hoc. Afterall, she characterized my paper as such: “However, going to this level of detail in my response is arguably unnecessary since even Bowers’ selective, post hoc analysis of the findings leads to the conclusion that there is stronger evidence in favour of using systematic phonics in reading instruction than not using it”. But instead she takes this finding as providing additional support for the long-term benefits of SSP, both in her comment and earlier work where she wrote: “Machin, McNally and Viarengo (2018) analysed student performance in the first five years after the English government mandated synthetic phonics and found that there was a significant improvement in reading among 5- and 7-year-old children across the board, with significant improvement for children from disadvantaged non-English speaking backgrounds at age 11” (Buckingham et al., 2019).

And as common, the exaggerated conclusions of the authors themselves are amplified by subsequent authors, such as Marinelli, Berlinski, and Busso (2019) who wrote:

“… a third fundamental insight from the recent literature shows that certain teaching practices can have a profound, beneficial impact on how students acquire basic skills. Three characteristics seem to explain and underlie effective teaching: i) the use of structured materials for teaching reading (Machin and McNally [2008]), ii) the use of phonics-based methods for teaching reading (Machin et al. [2018] Hirata and e Oliveira [2019]), and iii) the use of content targeted at the right level of difficulty for the student when teaching reading and math (Muralidharan et al. [2019], Banerjee et al. [2017]). “

See how this works?

With regards to the lack of improvement in the PISA outcomes in 2019, Buckingham writes: “There is little point discussing the PISA results in a great deal of detail. The cohort of 15 year old English students who participated in the latest PISA tests in 2018 were in Year 1 during the phased implementation of synthetic phonics policies a decade ago. They may or may not have had teachers who were part of the Phase 1 training”.

So, we seem to agree that the PISA data provide no support for SSP. But it is worth noting that Buckingham characterized the relevance of the study somewhat differently on twitter (Dec 1st, 2019) two days before the results were announced: “Hope England’s results have improved! Hard to know how much early reading policies might have contributed. This PISA cohort were in Reception and Yr 1 towards the beginning of SSP implementation and were pre-Phonics Screening Check. Lots of other good things going on too, though!”

Buckingham does agree that the PIRLS 2016 results are more relevant, but disagrees with my analysis of them. In response to the fact that Northern Ireland did better than England without legally requiring systematic phonics, Buckingham argues that Northern Ireland does implement systematic phonics, citing the current literacy strategy published by the Northern Ireland Department for Education (2011). Apart from dismissing the document I mention (easily found if you google it), she omitted the following passage from the document that she does cite (a passage immediately above the quote she provided): “A range of other strategies for developing early literacy should also be deployed as appropriate and pupils who have successfully developed their phonological awareness should not be required to undertake phonics work if the teacher does not think it necessary or beneficial”. It is also worth noting that Northern Ireland does not have a Phonics Screening Check (PSC), and according to Buckingham, the PSC played an important role in improving SSP provision in England (see below). Nevertheless, Buckingham wants to credit the success of Northern Ireland to the excellent provision of systematic phonics?

In addition, in response to the fact that the PIRLS results in England were similar to 2001 (pre SSP) and 2016 (post SSP) she cites some papers suggesting that the 2001 results were artificially high. Specifically, she quotes Hilton (2006) who wrote about the 2001 PIRLS “the sampling and the test itself to have been advantageously organised” and McGrane et al. (2017) who claimed that there was “relatively large error for the average score in 2001”. These are interesting points that should be considered, but I would note that there is no evidence I know of that the procedure for selecting children was different in subsequent years for PIRLS, and after looking through the McGrane et al report I see nowhere where they identify the “large error” (I’ve emailed McGrane and will update if he responds). At the same time, Buckingham dismisses a report by a well-respected researcher (Jonathan Solity) presented at one of the top conferences in reading research (Society for the Scientific Study of Reading) that showed that there was no increase in PIRLS results in state schools (the relevant population) from 2011 to 2016 (Solity 2018). This claim is easily verified or refuted by Buckingham if she cares to look at the PRILS report. And when she writes “For some reason, Bowers also makes an entirely unfounded statement about phonics instruction being “less engaging”, she must have missed the following passage in the paper “The PIRLS 2016 also ranked English children’s enjoyment of reading at 34th, the lowest of any English- speaking country (Solity 2018).”

Now perhaps Hilton (2006) is right and the published 2001 PIRLS results are inflated due to a flawed procedure in 2001 and not subsequent years, and perhaps Solity is wrong and the state school results are in fact higher in 2016 compared to 2011. And perhaps Buckingham is right, and excellent Northern Ireland PIRLS results did indeed depend on them implementing a strong version of systematics phonics in the absence of any legal requirement and in the absence of the PSC. But these are all explanation for why the English PIRLS results do not look better, not evidence that SSP has worked. Nevertheless, people have claimed that the PIRLS results support the efficacy of systematic phonics, such Sir Jim Rose, author of the Rose (2006) report, writing “the spectacular success of England shown in the latest PIRLS data” as further evidence in support of systematic synthetic phonics” (Rose 2017).

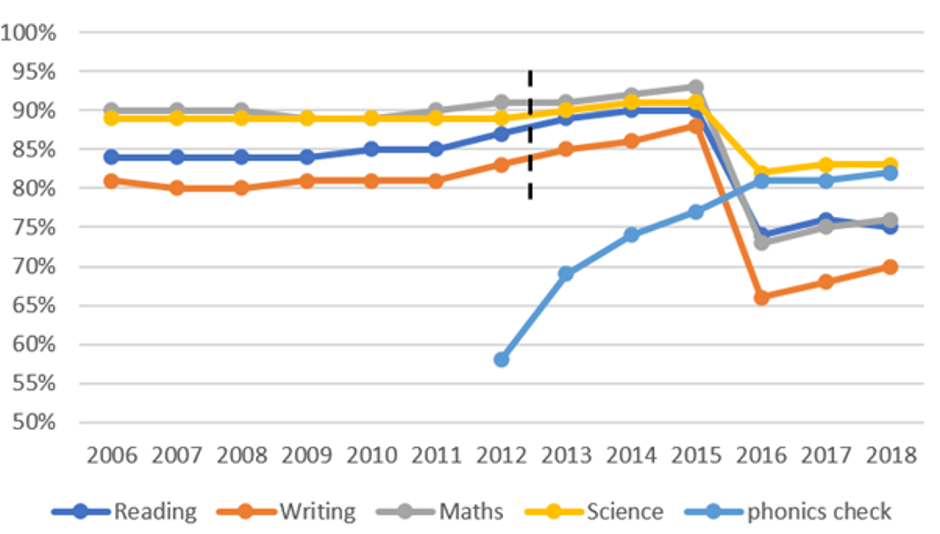

What about my claim that the SAT results in England provide no support for systematic phonics? Buckingham writes: “The graphs of KS1 and KS2 scores from 2006 to 2018 in Bowers (2020) clearly show an upward trend in reading and writing from 2011 to 2015 that is greater than the upward trend for math and science.” Given that Buckingham has expressed concerns about post-hoc reasoning in my article (without giving any examples), it is perhaps worth considering whether there is some post-hoc and motivated reasoning going on here. Consider the Figure 1.

The first thing to note is that there is no improvement in reading in writing in from 2006-2011 despite the introduction of SSP in 2007. When reading and writing results do go up from 2011-2012 (as large a gain in a single year as any) it is before the PSC is rolled out. Buckingham suggests that this increase might reflect the pilot PSC that was introduced a year before the PSC was officially implemented. When considering this hypothesis, it is worth noting that the pilot took place in 300 schools, as far as I can tell from report, included 9000 pupils. How this led to a nationwide improvement for 100,000s of children in reading and writing (as we as maths and sciences) in the SATs 2011-2012 is unclear.

The first thing to note is that there is no improvement in reading in writing in from 2006-2011 despite the introduction of SSP in 2007. When reading and writing results do go up from 2011-2012 (as large a gain in a single year as any) it is before the PSC is rolled out. Buckingham suggests that this increase might reflect the pilot PSC that was introduced a year before the PSC was officially implemented. When considering this hypothesis, it is worth noting that the pilot took place in 300 schools, as far as I can tell from report, included 9000 pupils. How this led to a nationwide improvement for 100,000s of children in reading and writing (as we as maths and sciences) in the SATs 2011-2012 is unclear.

From 2012-2015 (after the PSC) the outcomes for reading, writing, maths and sciences all steadily increased, and Buckingham suggests that the increased performance in science and maths might be attributed to the improved SSP due to the PSC writing: “It is not surprising that maths and science would also improve slightly as reading improves because maths and science tests require children to be able to read the questions proficiently.” But earlier in her commentary, Buckingham attributes the failure to obtain benefits in reading comprehension in all meta-analyses (apart from the short-term effect reported in the NRP) to the fact that many studies did not include instruction that develops language comprehension. Nevertheless, according to Buckingham, the improved delivery of SSP (due to the PSC) is potentially responsible for an increase in comprehension, that in turn improved the results of the math and science SATs. That seems a big post-hoc stretch.

The bottom-line is that the PSC scores improved dramatically from 2012 whereas the improvement in reading compared to nonreading SAT scores are TINY (look at graphs), with the improvements in SATs starting before the PSC was adopted. It is hard to conclude anything other than the introduction on the PSC led to improvements on the PSC and little or no evidence for improvements in PISA, PIRLS, or SAT results. And similarly, there is no evidence that the introduction of SSP in 2007 (long before the PSC) improved reading outcomes on these standardized tests. Indeed, the null results in the standardizes tests is in line with the lack of evidence for systematic phonics from the meta-analyses.

Before concluding I should also briefly address Buckingham’s criticism of SWI. What is so striking is, again, how she mischaracterizes basic points. Consider the following passage:

“The problem with seeing Structured Word Inquiry (SWI) as a superior alternative to systematic phonics is firstly that there is insufficient information to assess whether it is in fact based on the best available evidence. Bowers’ dismissal of what the vast majority of reading scientists accept about the essential role of learning GPCs in early reading acquisition suggests that it is not… If they do teach GPCs it would appear to be in a way that is more closely analogous to analytic than synthetic phonics, but in which the sub-word level analysis is based on morphemic units rather than sound units.”

How can Buckingham write “If they do teach GPCs” when we repeatedly emphasize the importance of GPCs in SWI instruction? For example:

Bowers and Bowers (2017) wrote: “SWI emphasizes that English spellings are organized around the interrelation of morphology, etymology, and phonology and that it is not possible to accurately characterize grapheme–phoneme correspondences in isolation of these other sublexical contraints” (p. 124) as well as writing “We have no doubt that learning grapheme–phoneme correspondences is essential” (p. 133).

Bowers and Bowers (2018) wrote: “To avoid any confusion, it is important to emphasize that the explicit instruction of orthographic phonology — how grapheme-phoneme correspondences work—is a core feature of SWI. However, unlike phonics, SWI considers grapheme-phonemes within the context of morphology and etymology.”

I have even directly tweeted Buckingham and emphasized the importance of GPCs in SWI, such as the following tweet: “SWI teaches GPCs from the start. In the context of morphemes. It teaches GPCs, morphemes, vocabulary together. More data needed to support hypothesis, but the evidence for teaching GPC by themselves is not strong”.

We do agree that more evidence is required for SWI, and we have made this point repeatedly.

To conclude, Buckingham is consistently wrong in her criticisms, often mischaracterizing the literature and my own work. I hope she responds, and of course, I welcome responses from others as well.

The science of reading is broken when applied to literacy instruction.

If Buckingham has been a reviewer on this paper it is clear she would have rejected it. And indeed, my paper was rejected by 4 journals and over 10 reviewers, almost all of whom recommended rejection based on a long list of mistakes and mischaracterizations. In a culture in which action editors are unwilling to even engage with authors in the face of straightforward factual errors from reviewers (until the action editor at Educational Psychology Review finally did), it is easy to block criticisms of systematic phonics in high-profile journals. Let me illustrate the problem by quoting the first lines of various letters I wrote to various editors of journals who (at least initially) rejected my paper.

For “Review of Educational Research” I wrote: “Dear **, I am writing with regards to the manuscript entitled “Reconsidering the evidence that systematic phonics is more effective than alternative methods of reading instruction” (MS-223) that was recently rejected in Review of Educational Research. Of course, it is always disappointing when a paper is rejected, but in this case, the reviewers have completely mischaracterized my work – every major criticism is straightforwardly incorrect, and barring one or two trivial points, so are all the minor criticisms as well.”

For “Educational Psychologist” I wrote: “It is disappointing to be rejected yet again based on a set of fundamental misunderstandings, mischaracterizations, and straightforward mistakes. Of all the criticisms, only one has any merit. I do appreciate that the repeated rejections (previously at Psychological Bulletin and Review of Educational Research) might suggest that the misunderstanding/mistakes are mine. But the same set of mistaken claims are repeated over and over, and my response to these errors are never addressed by the editors (who are not willing to reconsider their decision) or reviewers (who never get a chance to see my responses). There is an extraordinary resistance to a simple point I’m making – the strong claims regarding the benefits of systematic phonics are not supported by the data.”

For “Psychological Bulletin” I wrote: “Dear Professor **, I expected that my review of systematic phonics would be controversial, but I did not anticipate that the main objection would be that this work is of “limited interest to readers of Psychological Bulletin”. With Reviewer 1 claiming that “the main objective of the author(s) is to denigrate the National Reading Report (NICHD, 2000) and the Rose report (2006)”.

And for “Educational Psychology Review” (where the paper was initially rejected) I wrote: “Dear Professor **, I am of course disappointed that my article “Reconsidering the evidence that systematic phonics is more effective than alternative methods of reading instruction” was rejected at Educational Psychology Review, but it is also frustrating given that all the major criticisms are mistaken. In this letter I briefly highlight the major mistakes of the most negative reviewer (Reviewer 3). These are not matter of opinions, they are black-and-white errors that are easy to document. The other reviewers have not identified any important errors either, but I thought I would only comment on the most obvious mistakes of the most negative review to keep this letter reasonably short”. Here is a short excerpt from Reviewer 3: “Reading through the paper it becomes clear that the authors seem to have a strong bent towards non-systematic phonics and Whole Language”. You could not make it up.

I had a similar difficulty tying to publish a paper on SWI that was eventually published in Educational Psychologist (Bowers & Bowers, 2017). Again, it was rejected in multiple journals, and again, the same black-and-whole mistakes were repeated over and over by reviewers, such as the claim that we ignore the importance of teaching grapheme-phoneme correspondences (as claimed again by Buckingham).

I hope this long response will convince some that indeed the evidence for systematic phonics has been greatly exaggerated and make more people aware that the politics of reading research is biasing what gets published.

Bower’s article and subsequent response is a breathe of fresh air. The facts do not lie. It is a sad time when literacy stakeholders, politicians, and administrators believe opinion over research on such a large scale from people who clearly have products to sell and money to make off of states and districts. We’ve been through this before with Reading First (2000) when 6 billion dollars was spent on programs that provided no to negative effect on children’s reading achievement.