Anyone following my work will know that I’m not impressed with the research on phonics. But I am impressed by the motivated reasoning of leading researchers who claim that the science of reading strongly supports the importance of phonics and don’t see the gaping holes in the evidence. And even more impressed that most proponents of phonics ignore work that challenges the evidence. And more impressed still that I am yet to get a proponent of phonics to respond to a simple but direct (and polite!) request: “Can you provide me a reference to a study or meta-analysis that you think provides the best evidence for phonics?”. And I’ve asked quite a few experts.

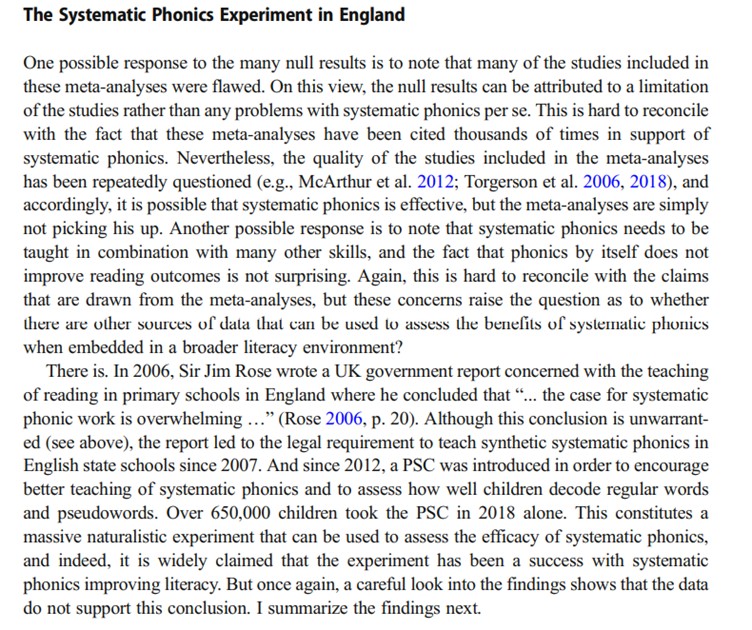

I’m writing this post in response to the furore that has erupted in response to an article by Wyse and Bradbury and an associated Guardian article challenging the claim that systematic phonics has worked in England. Let me start with a blogpost by Greg Ashman and a twitter exchange that ensued.

And indeed, he did. But more importantly, his blogpost is full of errors. One is particularly egregious:

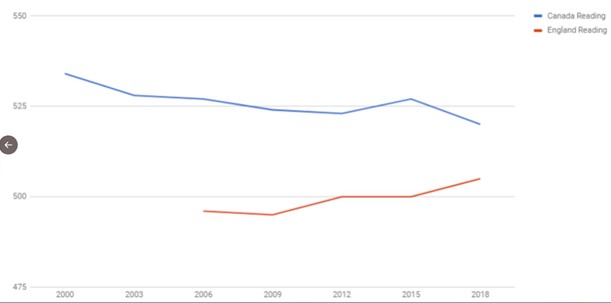

The graphs are hard to see on the screenshots from twitter, but here they are blown up.

First, here is Greg’s graph:

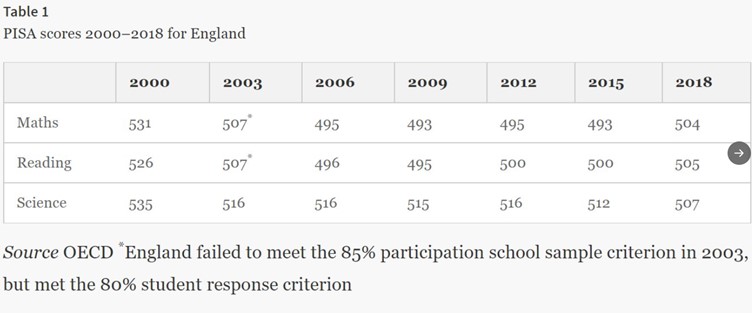

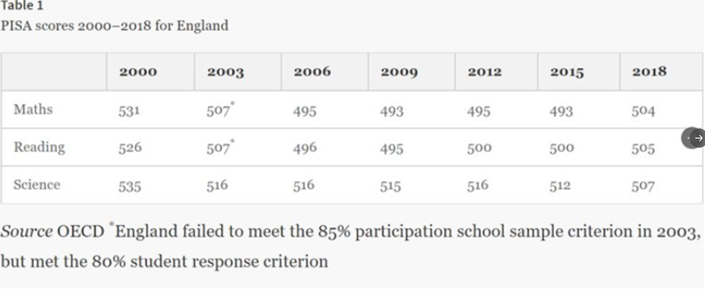

Second, here is a table that shows the results from England going back to 2000:

Do you see the problem? It is just poor science to selectively compare two out of multiple English-speaking countries, and even poorer science to exclude the UK results in 2000 and 2003 that mess up the story (England was doing much better in 2000, and still better in 2003 compared to 2018). I’ve asked Greg to update his blogpost to correct his error:

But nothing.

There are plenty of additional problems with his blogpost. For example, he challenges Wyse and Bradbury’s conclusion regarding the PIRLS results (an international test of reading comprehension). I tweeted the following with two screenshots attached:

Screen shot 1: What Ashman wrote in his blogpost:

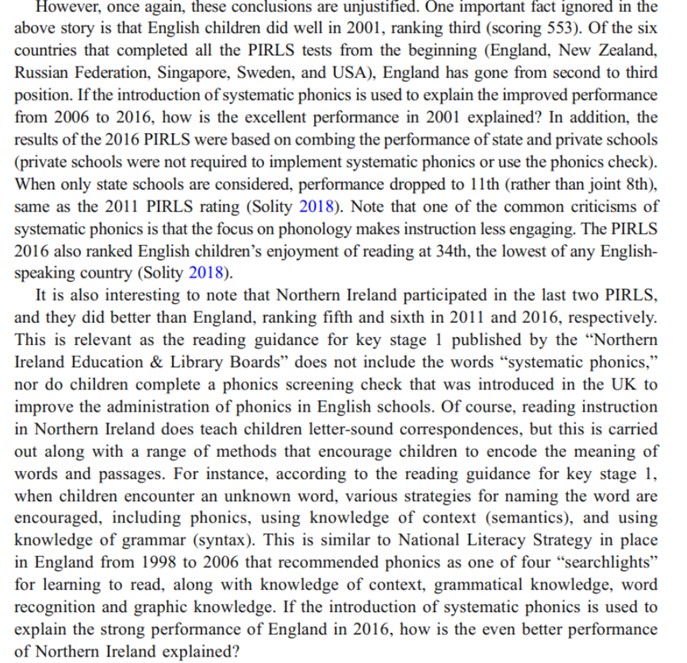

That is a lot of qualifiers — what does Greg mean by writing that the most recent PIRLS results “arguably showed significant improvements”? I tweeted him this passage of my work that considers the PIRLS results in more detail:

Screen shot 2: A passage from Bowers (2020) that shows that the PIRLS results provide no evidence that reading comprehension has improved in England:

Despite these and other problems, multiple prominent researchers write to congratulate Greg on his response. For example:

Shortly after Jennifer Buckingham wrote a blogpost full of mistakes and selective citations, and again, many endorsements followed. For example:

Here are the three images I attached to the tweet. The first depicts a graph by Stainthorp (2020) – a paper that Buckingham strongly endorces and takes as evidence that phonics has improved SAT reading results in England, the second is a graph I reported (Bowers, 2020), and the third image explains the difference:

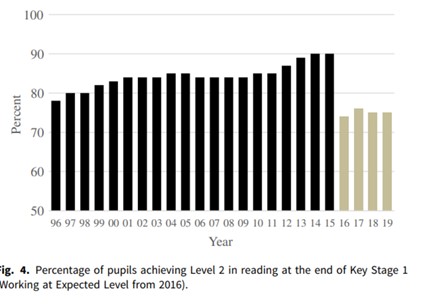

1) The Stainthorp (2020) graph. Note how the black bars start going up, consistent with improved reading outcomes (the test became harder in 2016, explaining the drop in performance, but the key conclusion is based on the black bars going up).

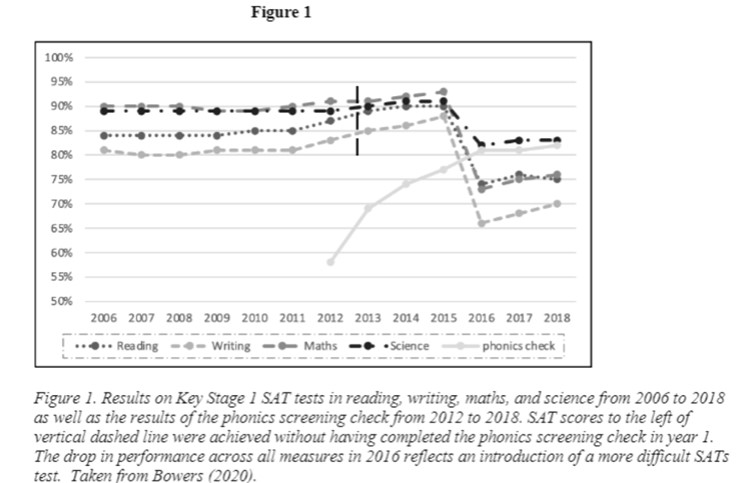

2) The Bowers (2020) graph. Note how the maths and science results go up at a similar rate as the reading and writing outcomes. And even worse for the story that phonics is responsible for the improved SAT reading scores, the timing does not work, as all scores start increasing the year before the introduction of the phonics screening check.

3) The explanation of key differences between graphs:

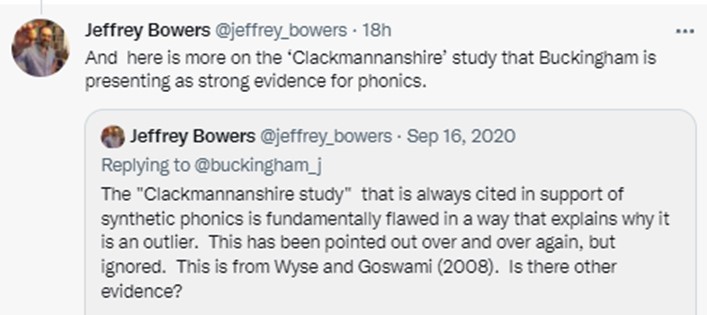

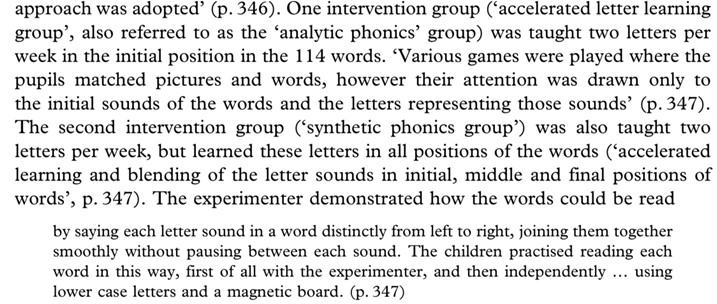

Regarding the Clackmannanshire study, Buckingham wrote in her blogpost: “Due to the very narrow (and, dare I say, not very systematic) method of selecting studies to review, one of the most important, and certainly most influential, studies of synthetic phonics instruction was left out – the ‘Clackmannanshire’ study in Scotland.” It has certainly been influential, but…. Here is a bit more detail I provided in an attachment to my next tweet.

It would be hard to find a more striking example of a confound that has been pointed out for years but that is just ignored. Indeed, I’ve directly pointed out this confound to Buckingham on twitter and she responded saying that she doesn’t think it is a problem (I can’t show this tweet exchange as I have been blocked). But it doesn’t stop Buckingham and many others from citing this work in support of systematic synthetic phonics.

A few days later Ashman comes up with another blogpost, again full of misrepresentations. This time, instead of calling Wyse and Bradbury liars, he suggests that they may be engaged in “deliberate misrepresentation”.

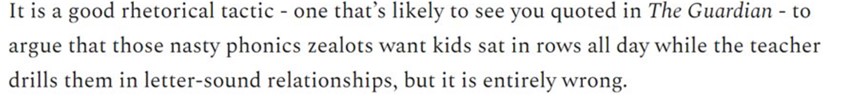

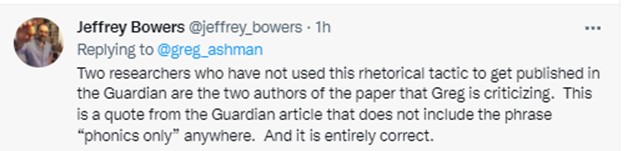

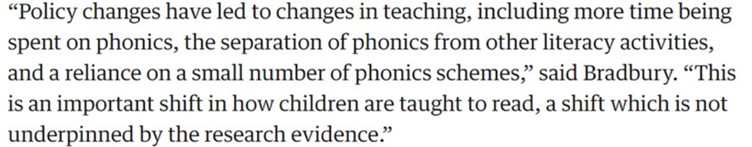

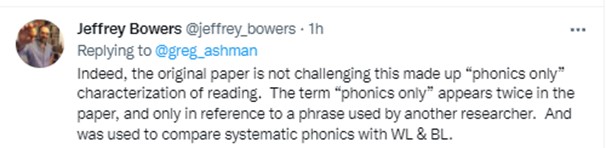

Ashman is not just engaged in hyperbole when characterizing the critics of phonics as thinking “nasty phonics zealots want kids to sit in rows all day…”; he fundamentally misrepresents the Guardian article and the published paper. Here are two tweets and attached images pointing out the problem:

Again, many endorsements from leading researchers. For example, Pamela Snow writes.

I continue to be struck by researchers who strongly endorse phonics and ignore straightforward mistakes that have been explicitly pointed out. No one has challenged any of the points I’ve made in these exchanges, and this is the norm, see: https://jeffbowers.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/blog/key-lesson/. Instead researchers just repeat the mistaken and misleading claims over and over again to their thousands of followers (and in published papers), and get annoyed when I have the gall to challenge them with evidence in public. I have to say I was disappointed in Dorothy Bishop who has done such great work on challenging poor scientific practice. See this excellent talk: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cQGD_Uw-Bj8&t=2s Indeed, Dorothy has written about a serious problem with the administration of the Phonics Screening Test: http://deevybee.blogspot.com/search?q=phonics+check But she will not engage with me regarding a more widespread problem with the science of reading, namely, the evidence for phonics itself.

There is a serious problem with the science of reading when it comes to reading instruction, but it is sure hard to get anyone to notice. For more fun absurdities, check out my other blogposts where you can find more of these twitter exchanges amongst other things: https://jeffbowers.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/blog/ You can download my freely available articles cited above at: https://jeffbowers.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/publications/education-literacy/

As always, it would be great to get a response, especially from the authors I’m criticizing. If I’ve made any mistakes, it would be good to know.

Addendum:

Ashman has responded to this blogpost (Response to Bowers – by Greg Ashman – Filling The Pail (substack.com)) and here is my response.

Ashman makes one reasonable point that was also made by James Theo on twitter:

This is with regards to the PISA graph that Ashman included in his blogpost that omitted the 2000 and 2003 data. I found it odd that these years were missing and quickly found a graph that included data for these years:

But as both Ashman and Theo rightly point out, there is some doubt about the accuracy of the 2000 and 2003 results given that England failed to meet the 85% participation rate in schools. This is from the Oates paper where this graph was taken:

In fact, I did include this qualification in the table above, but fair enough to point out, and happy to clarify this point. However, it does not address the problem of selectively comparing England to Canada, amongst other problems, as I previously wrote:

From: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10648-019-09515-y

Indeed, re-reading this passage and looking over the table again made me realize there is an additional reason why the Ashman graph is misleading. It not only omitted other countries, but it also omitted other outcome measures. And as you can see from the table, the increase in the Maths scores from 2015 to 2018 (the 2018 cohort were the first to receive legally mandated systematic phonics) was greater than for Reading (indeed, as noted in the passage pasted above, only the mean increase in Maths was significant). That rather weakens the basis for concluding that phonics was responsible for the improved reading outcomes. This is a similar problem to the Stainthorp (2020) graph I pointed out above. In this case, the graph selectively reported the SAT reading outcomes, and the increasing scores were taken to provide evidence that phonics was responsible. But again, other outcome measures (both Maths and Science results) improved as well, undermining this conclusion.

So, yes, I should have highlighted more clearly that the 2000 and 2003 PISA results are problematic as England failed to meet the 85% participation rate in schools, and I accept that Ashman had a dataset that did not include these data, explaining why he did not include these years in his graph. But the point remains, the PISA results do not provide evidence that phonics is improving reading outcomes in England.

Greg also rejects my critique of the PIRLS results, writing:

But this omits the many problems I noted in the passage above, including the first point regarding the 2001 results repeated here:

So, lets recap: There is no evidence that phonics has improved SAT or PISA results if you track all outcome measures, and no evidence that PIRLS results have improved since 2001. And as I detail in the paper below, there is also little or no evidence from intervention studies as summarized by all the meta-analyses carried out since the National Reading Panel (2000). The claim that the science of reading strongly supports phonics and that reading has improved in England since the mandatory teaching of phonics in state schools is not even close to being supported.

Bowers, J.S. (2020) Reconsidering the Evidence that Systematic Phonics is more Effective than Alternative Methods of Reading Instruction. Educational Psychology Review, 32, 681-705.

Moving away from the science of reading, Ashman does not like the fact that I criticize other researchers for endorsing his work.

My view is that senior and influential researchers should be willing to defend their endorsements of research claims that they share with 1000s of their followers. I’ve not challenged junior researchers, but people who have prominent platforms aiming to influence researchers, policy makers, and teachers alike. I have left the comment section open on this blogpost for them to respond.

Finally, I suppose I should respond to the following:

Again, here is the context:

Ashman is now clarifying that he was only pointing out a general lie that is often told about phonics instruction, not attributing this lie to Wyse and Bradbury (which would make them liars). Easy to misunderstand, good to hear that he was not calling them liars, and happy to retract this claim. I would just note again that the “phonics only” characterisation of phonics critics is a strawman, and the following an absurdity.

For example, this is a quote from my original critique of phonics:

Take from: Bowers, J. S. (2020). Reconsidering the evidence that systematic phonics is more effective than alternative methods of reading instruction. Educational Psychology Review, 1-25.

Finally, a simple truth. Everyone has a point of view, from the researcher who has a long history claiming the science of reading strongly supports phonics to the person who has a brother who puts forward data and arguments in support of Structured Word Inquiry, an alternative to phonics. The way to assess whether someone is engaged in motivated reasoning is to consider whether they: a) ignore contrary data to their position, b) mischaracterize data contrary to their position, c) fail to correct errors when pointed out, and d) fail to engage in debates on the topic. I give Ashman credit for avoiding d).

I hope the researchers I’ve criticised do post a response below or elsewhere, and as I’ve written many times, I would be happy to engage in a debate about the evidence for phonics online or in some other context. The science of reading has been used to justify the legal requirement to teach synthetic phonics in all state schools and England, and there is a strong push to put in similar regulations in Australia. Scientists should always avoid motivated reading as best as possible, especially so here given the policy implications.

It may be helpful to revisit Perfetti’s Lexical Quality Hypothesis. He writes:

“The LQH implies that variation in the quality of lexical representations, including both form and meaning knowledge, lead to variation in reading skill, including comprehension . . . For most readers, the problem cuts across meaning, orthographic, and phonological knowledge. The consequences of LQ can be seen in processing speed at the lexical level and, especially important, in comprehension . . . The source of LQ variation must arise through literacy and language experiences . . . These experiences include, among other things, learning to decode printed words, practice in reading and writing, and engagement with concepts and their language forms.”

The question we’re debating is whether phonics is the most efficient means we currently have of teaching children how to decode, not whether learning to decode will single-handedly facilitate reading comprehension in subsequent grade levels.

What is the best evidence that phonics is the best way to learn to decode? And what is the evidence that phonics *instruction* is a necessary part of reading instruction in order to facilitate reading instruction?

I’ll defer to Dorothy Bishop’s answer:

“So it’s all about making the best decisions we can, given the patchy evidence that we have – a point nicely made by Trisha Greenhalgh in the context of COVID-19.

The current debates have highlighted the shortage of well-designed studies to show which teaching method is most effective for which children at which age. As with medical interventions, studies also need to evaluate potential costs and harms – something which was neglected in the past, but which is relevant given that some of the disagreements are about whether particular approaches can be counterproductive.

But, as with Covid, policy decisions have to be pragmatic. This was the remit of the 2006 Rose Report, which attempted to synthesise evidence and expert opinion on reading intervention and came out recommending use of synthetic phonics. Overturning the status quo to radically change how reading is taught would only be reasonable if there was some other intervention approach for which there was better evidence of effectiveness – so much so that the costs of making a change would be justified. Maybe there is, but it hasn’t come up on my radar.”

I don’t strongly disagree with this: ““So it’s all about making the best decisions we can, given the patchy evidence that we have”. I think the evidence is less than patchy, but lets go with that. What policy decisions you make with patchy evidence is an important one, but it is not what I’m focused on. I’m pointing out that the evidence is patchy, and scientists should be straightforward about that.

I reread the Fletcher piece and your response. Unless I missed it, you didn’t respond to this claim, and I’m wondering whether you think this is part of what you call ‘less than patchy’ evidence.

“Stuebing et al. showed in their Table 2 (line 14) that if one only considers the relatively pure cases of interventions involving what the NRP defined as systematic phonics and compares these against conditions where Camilli et al. had coded the absence of both tutoring and wider language activities (85 contrasts in 17 studies), the effect size is d = .49. Arguing about whether the effects are small, medium, or large is not the relevant issue when making educational decisions about

whether some level of explicit phonics instruction is beneficial to learning to read.. Encouraging educators to discount positive effects of explicit phonics instruction is simply not helpful, but is potentially harmful to many children struggling to access appropriate reading instruction (Seidenberg et al. 2020).”

Hi Harriett, this is another quote from the Fletcher et al. article that is clearer: “As Bowers noted, Stuebing interpreted comparisons of no phonics, unsystematic phonics, and systematic phonics as a dosage effect, supporting this conclusion in their Table 2 where the effects of systematic phonics (d=.49) is larger than the effect of some phonics (d=.31) when the moderators coded by Camilli et al. are excluded from the comparison” So the effect of systematic phonics is not .49, but .49-.31 on this analysis. I do talk about the Stuebing study in detail in the original Bowers (2000) article. And more importantly, as discussed in that paper, when the RCT studies from the NRP meta-analysis are selectively considered, Torgerson et al. (2006) found the effects are mostly null (and the quality of the studies mostly poor, with evidence of publication bias). This is how the characterized the RCT studies included in the NRP:

…none of the 14 trials reported method of random allocation or sample size justification, and only two reported blinded assessment of outcome… all were lacking in their reporting of some issues that are important for methodological rigor. Quality of reporting is a good but not perfect indicator of design quality. Therefore due to the limitations in the quality of reporting the overall quality of the trials was judged to be “variable” but limited.

Jeff, does this analysis from a colleague seem accurate to you? If not, what is problematic?

On page 6, Bowers et al write:

“The most important limitation is that systematic phonics did not help children labelled “low achieving” poor readers (d = .15, not significant). These were children above first grade who were below average readers and whose cognitive level was below average or not assessed. By contrast, children labelled “reading disabled” who were below grade level in reading but at least average cognitively and were above first grade in most cases did benefit (d = .32). Note, by definition, half the population of children above grade 1 will have an IQ below average, and it is likely that more than 50% of struggling readers above grade 1 will fall into this category given the comorbidity of developmental disorders (Gooch, Hulme, Nash, & Snowling, 2014)”

The authors equate below average cognitive level with any score below the mean. As they say, half the children will have an IQ below average. Except, as anyone working with these measures now, the term below average is not used to describe any score below the mean of 100. Average is a range of scores, often followed by another range of scores termed low-average, before we get to scores termed “below-average.” It is most definitely NOT all scores below the mean, or half of all students as the authors claim.

This is abundantly clear if we read the relevant section of the report of the NRP that describes this finding. From page 2-94:

However, phonics instruction failed to exert a significant impact on the reading performance of low-achieving readers in 2nd through 6th grades (i.e., children with reading difficulties and possibly other cognitive difficulties explaining their low achievement). The effect size was d = 0.15, which was not statistically greater than chance.

This is a group including children with “other cognitive difficulties” that Bowers et al have repackaged as half of all students. The NRP further describes these students while noting the limitations of this finding. From page 2-94:

The conclusion drawn from these findings is that systematic phonics instruction is significantly more effective than non-phonics instruction in helping to prevent reading difficulties among at risk students and in helping to remediate reading difficulties in disabled readers. No conclusion is drawn in the case of low-achieving readers because it is unclear why systematic phonics instruction produced little growth in their reading and whether the finding is even reliable. Further research is needed to determine what constitutes adequate remedial instruction for low-achieving readers.

Note that the category “low-achieving readers” does not include disabled readers. Those are another group, a group that responded well to systematic phonics. These are students who read poorly, at least some of whom have “other cognitive difficulties explaining their low achievement”.

The report of the NRP warns us to draw no conclusions from these findings for a variety of reasons that are discussed in that section of the report. Nonetheless, Bowers et all have not only drawn powerful conclusions, that have badly misrepresented the data either because they didn’t understand it, or because doing so served their goals.

That error took me less than 5 minutes to locate. I have no doubt there are others, likely many.

Thanks for this, this is an example of someone making a substantive point. I do find it odd that this critic is only willing to spend 5 minutes on one of the few papers challenging his/her view, and who thinks a single error means it is not worth considering reading further. Would he or she apply this reasoning to pro-phonics papers I’ve identified with (multiple) errors?

But in any case, his/her point is not as strong as they think.

The author writes:

“The authors equate below average cognitive level with any score below the mean. As they say, half the children will have an IQ below average. Except, as anyone working with these measures now, the term below average is not used to describe any score below the mean of 100. Average is a range of scores, often followed by another range of scores termed low-average, before we get to scores termed “below-average.” It is most definitely NOT all scores below the mean, or half of all students as the authors claim.”

Except that in the NRP labelled “low achieving” in the following way:

“These were children above first grade who were below average readers and whose cognitive level was below average or *not assessed*”. [bold added]. So, it is not the case that this group of children were selected to have IQs below some range of scores. For instance, this is one of the studies:

http://www.lindalsullivan.com/pdf/Collaboration-San-Angelo.pdf

The author wrote the following:

“This is a group including children with “other cognitive difficulties” that Bowers et al have repackaged as half of all students. The NRP further describes these students while noting the limitations of this finding. From page 2-94:”

In fact, in the authors of the NPR wrote:

“children with reading difficulties and *possibly* other cognitive difficulties explaining their low achievement” [bold added]

Indeed, as I noted in my paper, children with reading difficulties will often be weaker in other domains, and of course, this is the population of students that need help more than any other.

This is what the author wrote: “The report of the NRP warns us to draw no conclusions from these findings for a variety of reasons that are discussed in that section of the report. Nonetheless, Bowers et all have not only drawn powerful conclusions”

What powerful conclusions? I’m claiming that the NRP provides no evidence that these children benefit from phonics. Is that wrong? This is what I wrote in Bowers (2020):

“Of course, additional research may show that systematic phonics does benefit low achieving poor readers (the NRP only included eight comparison groups in this condition), but there is no evidence for this from the NRP meta-analysis.”

But the “low achieving” category is vaguely defined, and the 8 different studies included in this category had different criterion for selecting children. Given that “low achieving” readers included struggling readers whose IQ were not even assessed, it seems reasonable to conclude that these results would apply to over 50% of the children who are struggling to read past grade 1. But I admit that the category of reader is vague, so it is reasonable to raise doubts on the 50% claim. Whatever the percentage, it would be substantial.

In any case, my argument does not hinge on no significant effect obtained for 50% of struggling readers above grade one. I’m claiming that there is no evidence from NRP that ANY children benefit on reading comprehension, fluency, spelling beyond an immediate test. And that subsequent research further weakened the claims of the NRP. I hope this reader will read for a bit longer and raise other concerns.

I’ve asked a colleague to cite some studies, so I’ll see what she comes up with. Here is her general response:

Inflectional and derivational morphemes (i.e., bound morphemes) need to attach to something and that something is a base word (also called a free morpheme). Letters by themselves don’t have meaning (for example, ED in RED doesn’t have any meaning; ED in PLAYED does). We first need to teach our students how to read (and spell) a base word (e.g., PLAY) before they analyze when reading (or attach when spelling) a cluster of letters that represent meaning (i.e., a morpheme), for example in the word PLAYED. If we don’t use phonics/orthographic mapping (in both the print-to-speech and speech-to-print direction) to teach reading and spelling of base words, how else do we teach this?

In Connectionist/Multilinguistic Models and Triple Word Form Theory, readers (and writers) simultaneously draw upon and coordinate phonological, orthographic, and morphological knowledge and skills to read (and spell) words; it’s a dynamic interplay with beginning readers/writers drawing more heavily on phonology and orthography and gradually relying more heavily on morphology. All three are needed, at the appropriate time and specific to a word itself. It’s not either—or. Black and white thinking is always problematic, especially when we’re talking about something as complex as reading and writing.

The terms ‘phonics’ and ‘balanced approach’ are used with befuddling imprecision by people on both sides of this debate. Is ‘phonics’ the same as ‘SSP’? Sometimes, yes, sometimes no. Is ‘phonics’ (or ‘SSP’!) ‘balanced’ because it includes meaningful engagement with text from the beginning, or not ‘balanced’ because it eschews all decoding cues other than GPCs? Sometimes the former, sometimes the latter. Folk on either side seem quite happy to skip the clarifying and jump straight to the insulting.

The great thing about the phonics screening test (PST) in England is that it is a concrete government policy, with data attached, that can provide a concrete point of discussion. Observers from other countries can avoid getting bogged down in terminological messes by asking, simply, ‘would this policy be good for us’?

Three cohorts of children have taken the PST in England and completed primary school in pre-covid conditions. They took the test in year 1, in 2012, 2013, and 2014 respectively.

The test results indicate that, across these three years, students and teachers together achieved a remarkable improvement in phonics know-how. In 2012, 58% of students ‘passed’ the test – this rose to 69%, and then 74% over the following two years.

(see page 3 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/851798/KS2_Revised_publication_text_2019_v3.pdf)

The results of the reading test taken at the end of primary school indicates how well these three cohorts fared over the following years. The 2012 cohort achieved a average scale score in reading of 104. The 2013 cohort achieved one of 105. The 2014 cohort achieved 104. In other words, the three year dramatic improvement in phonics knowledge at year 1 was pretty much entirely ‘washed out’ five years later.

(this data is taken from a UK Department of Education statistics circular, page 5, which you can see here: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/851798/KS2_Revised_publication_text_2019_v3.pdf)

The apparent lack of long term efficacy of improved phonics know-how is addressed by Jennifer Buckingham in a recent blog post (https://fivefromfive.com.au/blog/groundhog-day-for-reading-instruction/).

She writes:

“Good synthetic phonics instruction will get more children out of the blocks than would have been the case otherwise (in Kareem Weaver’s great metaphor) but it can’t guarantee they’ll finish the race, especially if its a marathon.”

I am not convinced by this metaphor. Ask any runner about the value getting out of the blocks in a marathon and they will tell you it is negligible – or they might say that marathons don’t even have ‘blocks’ – for precisely this reason. The data from England certainly suggests that reading is indeed a marathon, and that the improved start initiated by phonics screening checks (which I would not dispute) is relatively unimportant for long term literacy.

I only hope that the advocates of a phonics screening check in other jurisdictions are transparent about the fact that, if the England example is anything to go by, it will not lead to improved reading scores at Grade/Year 6 and beyond.

Might this help to explain the 2019 KS2 reading results? –

https://schoolsweek.co.uk/dfe-urged-to-give-more-time-for-ks2-reading-test-after-word-count-soars

Great post!

“The data from England certainly suggests that reading is indeed a marathon, and that the improved start initiated by phonics screening checks (which I would not dispute) is relatively unimportant for long term literacy.”

This is quite a leap! I work with small groups of struggling first and second grade students three times a week to get them ‘out of the blocks’ so that they develop word recognition skills. Once a week I teach a whole class of third graders. As a teacher in the trenches, I can tell you for certain that I am able to take my third graders who can decode quickly and efficiently to a deep understanding of complex grade-level text through analyzing that text and synthesizing a response to it–what I also did when I taught high school. However, my third graders who still struggle with word recognition do not have a ‘relatively unimportant’ handicap–they are seriously crippled. If they can’t read the words, they can’t understand the text. Our job is to find the best ways to help them do both.

I like how Dorothy Bishop frames the discussion:

“Overturning the status quo to radically change how reading is taught would only be reasonable if there was some other intervention approach for which there was better evidence of effectiveness – so much so that the costs of making a change would be justified. Maybe there is, but it hasn’t come up on my radar.”

I watched that ‘rain’ video several times when Pete Bowers recommended it during some correspondence we had two years ago, and I reacted very much like Harriett. When children who can’t yet read the word ‘rain’ are taught the SWI way from Day 1, how do they perform on standardised tests of reading and spelling 6 months later or a year later?

It is a fair question, and more empirical work on SWI should be carried out. Here is a study that provides evidence that SWI is more effective than phonics in 5-7 year olds, but it did not assess outcomes a year later.

Devonshire, V., Morris, P., & Fluck, M. (2013). Spelling and reading development: the effect of teaching children multiple levels of representation in their orthography. Learning and Instruction, 25, 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2012.11.007

Thanks – I know that paper. The children had variously been given one year or two years of instruction on a synthetic phonics programme which I helped to write, ‘Letters and Sounds’, published by Labour in 2007. It was not very faithfully implemented, judging by information in the Devonshire et al. paper, but the children can’t be cited as examples of children taught by SWI from Day 1 without any prior or concurrent synthetic phonics instruction. Those are the children I’d really like to know about.

Thanks Jeffrey.

As always your contributions make me think. But every time, I run into the same problem, which stops me in my tracks. I honestly believe that many of use do not have the same understanding of the word phonics.

Can you please let us know if “teaching phonics” and “teaching sound:symbol correspondences” are synonymous?

The answer to this, I think, may explain a good deal of the “disconnect” between many researchers in the area of reading acquisition, and your often interesting analysis of large scale assessments of reading outcomes toward the end of secodary schooling.

Are “sound:symbol correspondences” and “phonics” the same thing?

Sara

Hi Sara, phonics is a specific approach (or a family of approaches) of teaching letter sound correspondences, but it is not the only way. I’ve detailed this point in the following paper, and below is an extract. But even if you reject this definition, the issue still remains: there is no good empirical evidence that phonics works when accepting the definitions of all the authors of the meta-analyses and the curriculum in England.

A key point emphasized by Bowers (2020) is that all forms of systematic (or explicit)

phonics teach letter-sound correspondences before and independently of the meaning-based regularities in spellings (morphology and etymology), what Bowers and Bowers (2018b) called the “phonology first” assumption. That is, teaching of GPCs in phonics is not informed by the fact that English spellings encode both phonological and meaningful regularities, with morphology constraining GPCs. The centrality of this claim to phonics is not only highlighted by the many statements that morphological instruction should follow phonics (e.g., Adams 1990; Castles et al. 2018; Ehri and McCormick 1998; Larkin and Snowling 2008; Frith 1985; Rastle 2019; Rastle and Taylor 2018; for a challenge to these claims, see Bowers and Bowers 2018b) but also by the fact that not a single phonics intervention in all the meta-analyses described below taught children the interaction between morphology and phonology. In addition, advocates of systematic phonics often justify the phonology first hypothesis on the basis of the “simple view of reading” (Hoover and Gough 1990), according to which children need to first decode written words before accessing word meanings via their verbal language system, and on the basis of the “alphabetic principle” according to which children need to first “crack the alphabetic code” that maps graphemes to phonemes (e.g., Castles et al. 2018).

But phonics is not the only way to explicitly teach GPCs. For example, Structured Word

Inquiry (SWI) teaches GPCs in the context of morphology in an attempt to teach GPCs more effectively. SWI is not an example of adding morphology after teaching GPCs, or even an example of teaching GPCs and morphology at the same time but independently. Rather, it is an example of teaching GPCs and morphology together, from the start, at the same time, because they interact in ways that make sense of GPCs…

From: Jeffrey S. Bowers (2021). Yes children need to learn their GPCs but there really is little or no evidence that systematic or explicit phonics is effective: A response to Fletcher, Savage, and Sharon (2020). Educational Psychology Review. doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09602-z

You say, Jeff, that ‘SWI is not an example of adding morphology after teaching GPCs, or even an example of teaching GPCs and morphology at the same time but independently. Rather, it is an example of teaching GPCs and morphology together, from the start, at the same time, because they interact in ways that make sense of GPCs.’

You and I are both in England, where almost no children have yet turned 5 by the time they have their first reading/spelling lesson in school, and many would not know any GPCs. Can you outline what the first SWI lesson would teach those children in terms of GPCs, morphemes and the way they interact?

Yes I can, and I’ve done multiple time, for example: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s10648-021-09602-z.pdf

But this is not a blogpost about SWI, it is about the evidence for phonics. You should comment on some of my other blogposts if you want to focus on SWI.

Here’s how I would characterize the impasse, Jeff. You ask “What is the best evidence that phonics is the best way to learn to decode?” and you haven’t been convinced by the answers. We ask “Can you outline what the first SWI lesson would teach those children in terms of GPCs, morphemes and the way they interact?” and we haven’t been convinced by the answers. Surely, there must be a first lesson. I remember my first lesson seven years ago when I taught kindergarten. Videos about eggs, cats and dogs do a good job pointing out plurals, but they don’t actually provide a lesson for teaching students how to read a word. Just yesterday, I took a group through the words helped, handed, and grabbed, which featured in their story. As English learners, they tend to leave off endings or say ‘help-ed’ the way you would say ‘hand-ed’. BUT these kids were able to use their phonics skills to blend the words, and then I could remind them to blend through the entire word and also point out the varying pronunciations for ‘ed’.

You’re frustrated that you’re not getting the research you request. We’re frustrated that you’re proposing an alternative to phonics without giving us the blueprint for what it looks like in a lesson format (I couldn’t find a beginning lesson in the link you gave). One colleague asked a good question: “Will SWI be held to the same standard of proof as SSP. If so, it hasn’t even got out of bed yet!”

Harriett and I again see things very similarly. I realise that the blogpost itself was not about SWI, but SWI has been mentioned in the comments, and I therefore felt it was reasonable to ask about it.

I’ve re-read your ‘Yes children need to learn their GPCs..’ article, Jeff, most of it quickly but the last part more carefully, as that seemed to be where I was most likely to find the sort of answer I was hoping for – an answer which specifies the GPCs, morpheme(s) and type of interaction which might be taught in the very first lesson for Reception children in England – (children aged 4-5, not 5-7 as in the Devonshire et al. study). I didn’t find those details, however, and I’m therefore having to envisage what is involved – enough GPCs for a base word and any additional morpheme(s) to illustrate the interaction. I think Harriett and I are saying that few if any of the real beginners we’ve worked with would grasp and retain much of what I’m envisaging.

This blogpost is not about SWI, but feel free to write more about SWI in other blogposts of mine where I do focus on SWI. I’ll just say one final thing about SWI in this blogpost and then restrict my comments to issues regarding phonics. Proponents of the phonics of reading claim there is strong evidence (sometimes “overwhelming”) evidence for phonics, and this has led to the legal requirement to teach phonics is England. I have challenged the evidence, and suggested another approach, that also teaches GPCs, but in a different way. There is only one study to date that has directly compared phonics and SWI in young reader (ages 5-7), in a RCT, and it reported significant advantage for SWI. But that said, it is a single study, and more research needs to be carried out. That is why I am not claiming there is strong empirical evidence for SWI. I’m claiming that given the poor evidence for phonics, we should consider alternative methods.

“I’m claiming that given the poor evidence for phonics, we should consider alternative methods.”

In order to consider alternative methods for beginning reading instruction such as SWI, I’ll need to examine a teacher’s guide. Where can I get one?

You mention ‘the legal requirement to teach phonics in England’, Jeff.

Justification for systematic phonics instruction was provided by the 2006 Torgerson, Brooks and Hall review, commissioned by what was then the Department for Education and Skills. The review concluded that ‘Systematic phonics instruction within a broad literacy curriculum appears to have a greater effect on children’s progress in reading than whole language or whole word approaches. The effect size is moderate but still important. However, there is still uncertainty in the RCT evidence as to which phonics approach (synthetic or analytic) is most effective’. The review then recommended that ‘systematic phonics instruction should be part of every literacy teacher’s repertoire and a routine part of literacy teaching’ for all children. The 2006 Rose review went a bit further in recommending synthetic phonics, but that was because the review team had been more impressed with it than with the alternatives during classroom visits.

The government programme ‘Letters and Sounds’ was then published in 2007, but there was no legal requirement to use it or any other particular programme. There WAS a legal requirement once the 2014 National Curriculum came into force, however. In both that and ‘Letters and Sounds’, the initial emphasis was on teaching GPCs and how to apply them in reading and spelling, but both also included some emphasis on morphology – no later than Year 2 in ‘Letters and Sounds’ and in Year 1 in the National Curriculum, so just as early as SWI started in the Devonshire et al. study. Both publications, incidentally, included rules taught in the SWI intervention used with Year 3 and 5 children in the Colenbrander et al. (2021) study, which you co-authored, Jeff – e.g. those to do with dropping final ‘e’, doubling consonants and changing ‘y’ to ‘I’. In fact that study states that ‘instruction in prefixes, suffixes and morphological spelling rules is mandated as part of the UK Grade 3 spelling and grammar curriculum’ (p. 326). Yes – and it’s mandated from Year 1, which is the earliest year in which the National Curriculum is applicable.

So the difference between SWI and what is mandated in England is to do with WHEN not WHETHER morphology is taught, and there seems to be no evidence, as yet, that it’s better to do it from the very start of instruction.

I like the simplicity of this statement from a reading researcher, which is confirmed by my many years teaching beginning readers:

“It is important that readers can decode and recognize base words before they must attend to the added complexity of a base word with a suffix.”

Here’s where I think you’re making your mistake, Jeff. A huge one that could impact the lives of many vulnerable children if you successfully undermine phonics instruction. Please excuse the melodrama, but if you read or watch anything by Kareem Weaver (like this 3-minute video) https://vimeo.com/538878822/5b22afb0dc?fbclid=IwAR1N_LF33uuYV6WmCVOymUY5-i9JBFuNDAjPb51Qp8mrzcCEJ2xm0lhRXRs, you’ll know how high the stakes are. As I’ve told you before, I’ve watched all the interviews you and Pete have given and also watched videos of what SWI looks like for beginning readers. Those of us who have taught hundreds of children how to read know how cognitively taxing SWI would be for most children. It’s no wonder that one of the schools here in the S.F. Bay Area that has adopted SWI also requires an IQ test as part of its admissions process.

You say in your “The Science behind the Story” piece that “nothing motivates more than understanding.” I couldn’t agree more, which is why when my first graders crack the code and are able to read those squiggly lines on the page and understand the words they represent, their eyes light up. You insist that “all GPC’s can be taught explicitly . . . using morphological matrices for a wide set of interesting word families, so that children learn GPC’s, word spellings, and vocabulary at the same time.” To reduce the cognitive load, I find that just dealing with spelling variations is quite enough for my beginning and/or struggling readers. Today we read “Fox and the Green Grapes”, and while I do want my students to know the meanings of the words with the variations for /ee/ (dream, reach, sunny, funny, silly, breeze, sweet) that they will encounter in the text, I don’t want to add to their burden by asking them to process more than they can handle. This is where I do agree when you say that “even if you take the view that learning GPC’s is the key for ‘cracking the orthographic code’ (which I do) “it makes sense to learn these correspondences in the context of spelling and vocabulary instruction”. What you fail to mention is that, by necessity, vocabulary will be constrained at first by the simplicity of the text–though my first graders did recently learn what a fig is through one of their stories.

I noted in several responses to the Wyse and Bradbury piece the objection that phonics studies with struggling readers were omitted. If that is indeed the case, then this is a serious omission since I maintain that most of what you describe is too taxing for struggling readers. Your video of how kindergartners ‘investigated’ the ‘rain’ family is a good example of ‘talking about words’ rather than actually ‘reading the words’. I have intervention students who are still struggling with recognizing ‘ai’, so adding the burden of ‘ing’ is not where I want to go initially. You decry the use of nonsense words on the UK Phonics Check, whereas I think using alien names is a stroke of genius, and I’ve adopted and adapted them to suit my needs. I have never had students smile through an assessment the way many of them do now. Sure enough, my second graders who didn’t recognize ‘waib’ (a plump pink alien) could also not read ‘rain’. As for ‘blem’ (the leggy blue one) it’s part of the real word ‘blemish’, isn’t it? Don’t I want my students to ‘chunk’ multi-syllabic words like ‘probably’, which they may not realize they actually know?

You also lament that “researchers who advocate phonics repeatedly highlight how phonics is not enough” but that you are “not aware of any of these researchers citing the morphological matrix or other tools of SWI that can be used for instruction after phonics.” I can’t speak for others, but there is a wonderful online matrix-maker, which I use for the students I teach in grades one to three. So if it is indeed the case that the morphological matrix is “almost completely neglected in instruction,” then that is unfortunate.

Do I think the ‘science of reading’ movement has gone too far? Absolutely. Do I think there is too much overcorrection? I do. Do I wish we’d follow Mark Seidenberg’s recommendation regarding phonics (Get in, get out–move on!)? You bet. But I also think your campaign to ditch phonics without a viable alternative is reckless and misguided. And that’s your biggest mistake.

Hi Harriett, thanks for taking the time to respond, but I think there is an important point you are not fully appreciating. SWI *does* teach GPCs explicitly, just differently than phonics. The question of this blogpost is whether there is strong evidence that phonics is working better than alternatives, and I don’t think there is. I do agree that more evidence is required for SWI.

Regarding the difficulty of SWI, I just think it is a misunderstanding how early instruction with SWI works. Here is a nice video that shows how SWI instruction is engaging, and no reason to claim that working memory load is overloaded: https://vimeo.com/189070725 This video was made at the school you mention that is highly selective, but SWI is being taught at multiple schools around the world (just not in England where phonics is legally required at the start, and a general lack of interest later). SWI does not require children with high IQs, because all children learn best when information is presented in an organized and meaningful context.

“ditch phonics without a viable alternative” is a hyperbolic falsehood.

Phonics is not the only way to study orthographic phonology, but it is likely to be rife with misinformation and falsehoods about the language.

Thanks for the link, Jeff. I always follow-up on your suggestions. This video I’ve seen before and is a great example of how we are referring to two different things. This lesson about word families has a wonderful oral language component matched to morphology. Great stuff. But it’s what I call ‘talking about words’ rather than ‘reading words’. My struggling readers can happily engage in this lesson. Sadly, they can’t read the word ‘rain’.

Hi Harriett, I’ve heard several people ask similar questions to, ‘What would the first lesson in a SWI approach be?’. I’m just a beginner in understanding orthographic linguistics and how word inquiry, ala a structured word inquiry approach, would work in a classroom. I wish I had stumbled across SWI long before I left primary school teaching after 25 years. A SWI approach is about teaching morphology, phonology, and even etymology from the start, but it doesn’t mean bombarding students with a lot of information all at once in their first lesson. I find the first lesson question a bit odd really, because the first lesson in teaching students about reading and how to read words surely doesn’t dive straight in to learning the GPCs in words in books. BUT if we are talking about a first lesson in GPCs that students might read in a book then surely it depends on the resources you are using. If you are using texts with strictly controlled GPCs then your first lesson is likely to be very different to a teacher who is using an orthographic linguistics approach (with children’s literature) to teach students how to read AND write words. David Hornsby (somewhat) describes planning to teach GPCs with a focus on meaning and morphology as well as phonology and alphabet knowledge in an article at https://davidhornsby.net.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Hornsby-2018-Prof-Educator.pdf I’ll have a go at thinking through a ‘first’ lesson in GPCs and morphology here in the following… If you work on a picture book with a dog character then you would model how to speak, write, and then read a sentence using the word ‘dog’. You might write the letters in the word ‘dog’ as you speak each sound in the word (direct GPCs teaching there). Believing that introducing the names of letters helps you talk about the content you are teaching, you could then make explicit the GPCs with more work on announcing the letters, sounding the spoken sounds those letters represent (in this simple CVC word), but you might extend this then to talking about ‘dogs’. In a follow-on (activity/lesson) you would write and indicate to the students that there is another letter now for the /z/ sound, and you’d discuss how the letter is needed to indicate a plural/more than one dog. You could then talk about (the meaning of) and write a couple of other words that rhyme with , such as and (togs = a swimming ‘costume’ where I come from) and include the word . You would announce the letters and talk about out the sounds that these letters are representing in the written word – which would bring in the understanding that a letter ( this time) does not always represent the same spoken sound in written words. As David Hornsby points out, you would continue teaching content using a planned (‘systematic’ if you like) approach, knowing which texts you wish to use to help you model the reading and the writing of words. In a planned approach that doesn’t follow a set program you would use an sequence of content that is personalised for individual children or groups of children. The learning experiences should also involve incidental teaching as well, as opportunities present themselves. I hope this all makes sense. Slightly cross-eyed with fatigue here so excuse any errors.

Oh SIGH… I must have wiped some of what I wrote, in the posting!

EDIT part of my text above:

You could then talk about (the meaning of) and write a couple of other words that rhyme with , such as and (togs = a swimming ‘costume’ where I come from) and include the word . You would announce the letters and talk about the sounds that these letters are representing in the written word – which would bring in the understanding that a letter (this time ) does not always represent the same spoken sound in written words.

OKAY… SIGH and double sigh… apparently words within angle brackets disappear!!!!!

EDITED again:

You could then talk about (the meaning of) and write a couple of other words that rhyme with dogs , such as logs and (togs = a swimming ‘costume’ where I come from) and include the word slogs. You would announce the letters and talk about the sounds that these letters are representing in the written word – which would bring in the understanding that a letter ( this time s ) does not always represent the same spoken sound in written words.

Thank you so much, Narelle, for taking the time to describe this sequence. Having taught hundreds of children how to read, I am very sensitive to cognitive overload and do everything I can to simplify the process for them, especially for those who struggle because they lack literacy experiences in the home or have other challenges. I believe what you describe adds unnecessary complexity to the process of learning how to decode. Yes–we extract words from the books we read and work with those words prior to reading the text. But even more fundamental and foundational, we work on the process of blending and segmenting phonemes and do all this before adding other layers of instruction. This is the foundational skill that students can apply to every word they encounter, adding in, of course an understanding of morphological markers to aid in their comprehension. Thanks again.

I think that you’ve done a very helpful job in designing what you think that first lesson might look like. I do have a few questions.

First, in my teacher training it was emphasized (and I believe correctly) that you start with planning what you want students to know and be able to do, and to develop your lesson plan(s) to reach those objectives. Then you select the best materials for those teaching objective. So where you suggest that it starts with the materials you are going to use, I would hope that would not be the case. I choose materials based on what I want children to learn. Is that different from your general approach, and if so, can you help me to understand your lesson planning method?

Separate from that though, let’s assume that you are right, and the materials I am going to use make it important for the child to be able to read (and spell – the way I teach) the word (working both from, and to, print).

It looks like you and I would both probably start by connecting the print (graphemes) to the sounds (phonemes). For example, you said:

“You might write the letters in the word ‘dog’ as you speak each sound in the word (direct GPCs teaching there).”

So, your method in this example, is a ‘phonology first’ approach to decoding a word. Once the base is known (GPCs and phonology connecting the print to meaning the children have for that word from oral language) THEN we immediately can begin discussing morphology. Am I right?

Sara

“‘You might write the letters in the word ‘dog’ as you speak each sound in the word (direct GPCs teaching there).’

So, your method in this example, is a ‘phonology first’ approach to decoding a word. Once the base is known (GPCs and phonology connecting the print to meaning the children have for that word from oral language) THEN we immediately can begin discussing morphology. Am I right?”

This makes sense to me, Sara. Jeff, what about this sequencing would you find problematic?

How can phonics (the teaching of relationships betw. sounds and spellings) help with learning to read and write with a spelling system which poses learning difficulties because its sound-to-letter links are unreliable – http://englishspellingproblems.blogspot.co.uk?

Instead of arguing about teaching methods, which none really differ greatly, we should be looking into making English spelling more learner-friendly. The decades old reading wars have done no good whatsoever. Overall failure rates have stayed much the same in all Anglophone countries for the past century, because the number of words with stupid spellings has stayed the same.

Spelling reform?

>Yawn.<