This post is inspired in part by a recent blogpost of Dorothy Bishop entitled “Why I am not engaging with the Reading Wars” (http://deevybee.blogspot.com/2022/01/why-i-am-not-engaging-with-reading-wars.html) where she expresses some annoyance at me for bringing her into a debate that she is not focused on. I have been arguing that the “science of phonics” suffers all the faults (and more) of bad science that Bishop has written about and described in this excellent talk: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cQGD_Uw-Bj8&t=2s , and it was in that context I was hoping to get her take on the evidence. But showcasing her unwillingness to engage in this debate in my previous blogpost did not go over too well, nor did my response to her blogpost, with Bishop concluding that “she is not an academic gun-for-hire”.

The thing is I respect Dorothy Bishop, and perhaps I did get a bit out of line here. I discuss this a bit more below. However, the point of this post is not to apologize, but to reflect on whether my tactic of publicly challenging prominent researchers and people active on social media is an effective way to respond to the bias in the field. I certainly am not making many friends, I think I’m losing some, and there are not too many signs that I’ve changed anyone’s mind.

In my view there are 3 basic reasons why the normal approach to science does not work here, namely: I would not have been able to publish my work in peer reviewed journals; my published work would be largely misunderstood given the many ways it has been grossly mischaracterized; and my work would then largely be ignored. This is the context in which I’ve started calling people out. A key reason why my brother Peter Bowers and I are willing to speak out is that we can afford to burn our bridges with the science of reading community (although we don’t want to). I’m a senior professor where most of my work is in other areas, and Peter is not in academia. It would be difficult for a junior researcher to challenge phonics with evidence and keep his or her career on track. That is a problem.

The three reasons why I have responded so forcefully

1) It is near impossible to challenge the evidence for phonics in a top journal in the normal manner. It is important to understand that the “reading wars” does not refer to an acrimonious debate between two different camps of researchers in psychology or educational psychology. In the research world, there is near universal consensus that the science strongly supports the conclusion that systematic phonics is necessary, and consequently, almost all editors and reviewers of “top-tier” journals have a strong prior in favour of phonics. In my case, every paper I’ve published (bar one) challenging the evidence for phonics or proposing an alternative approach (Structured Word Inquiry) was rejected (often at multiple journals). I only succeeded in publishing work by challenging the arguments of the reviewers and counting on the rare action editor who would consider my arguments and be willing to change their decision. The lone exception was my paper co-authored with Peter Bowers published in Current Directions in Psychological Science where I was invited to write an article on a topic of my choice (Bowers & Bowers, 2018).

It is hard to overestimate the degree of bias in the review process when challenging the evidence for phonics. For example, here is the beginning of my letter to the editor Review of Educational Research where my review of phonics was eventually published (Bowers, 2020):

“Dear **, I am writing with regards to the manuscript entitled “Reconsidering the evidence that systematic phonics is more effective than alternative methods of reading instruction” (MS-223) that was recently rejected in Review of Educational Research. Of course, it is always disappointing when a paper is rejected, but in this case, the reviewers have completely mischaracterized my work – every major criticism is straightforwardly incorrect, and barring one or two trivial points, so are all the minor criticisms as well.”

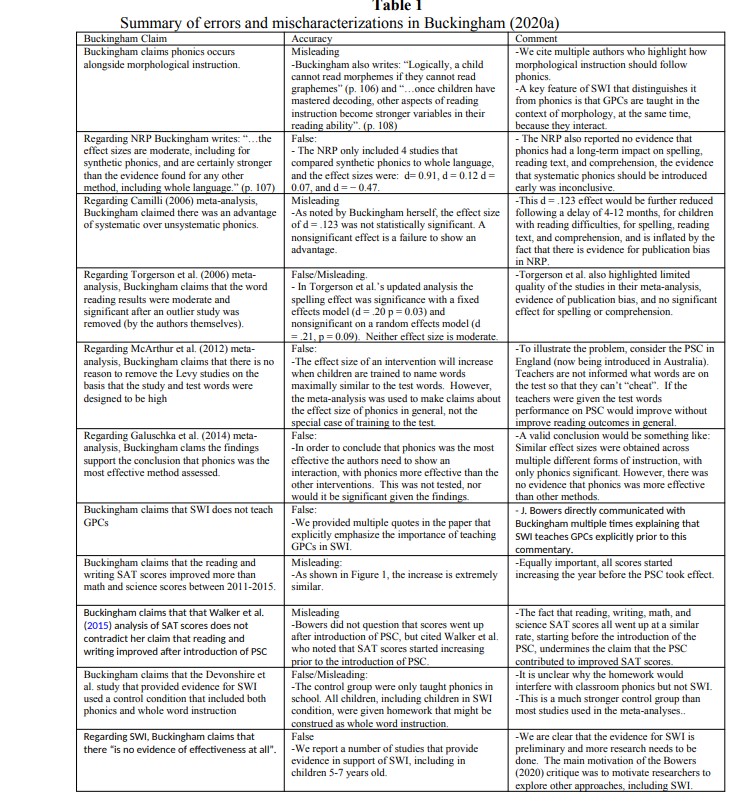

Indeed, for all my published papers in this area, almost all the reviewers’ comments were just wrong. This no doubt sounds an outlandish claim, and I’ve been tempted to publish the reviews and exchanges that followed, but they are awfully long (you would have to be a bit obsessive to read it all), and I felt a bit uncomfortable publishing the correspondences that were not intended for public consumption (yes, I know, I did publish this: https://jeffbowers.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/blog/buckingham-2020/). But luckily (?) there is one example I can point to, namely, Buckingham’s (2020) response to my phonics article published in The Educational and Developmental Psychologist that I was not asked to review. Not only is every major point in her published article wrong or misleading, but most of the errors were repeated from an earlier blogpost that I did respond to (https://jeffbowers.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/blog/buckingham/). I’ve summarized all the errors and highly misleading statements in Table 1 in Bowers and Bowers (2021), and so far, Buckingham nor anyone else has responded to a single point.

Buckingham’s review article is not so different from many of the reviews I’ve received, and if I just followed standard practice, and quietly accepted the decision of the action editors, little of my work on phonics or Structured Word Inquiry would have been published. But I did push back, and occasionally an action editor would read my rebuttal and not simply respond that the reviewers were expert in the field and the decision was final.

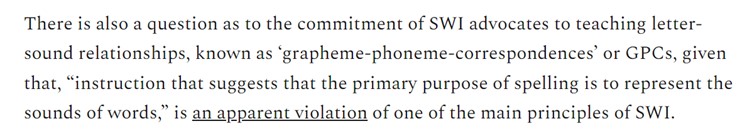

2) I expected publishing this work would be a challenge, but I was not expecting that so many prominent researchers, blogpost writers, and especially tweeters, would misrepresent our work. The misrepresentations are perhaps the most outrageous in social media as detailed in earlier blogposts. But the published misrepresentations are striking as well. One of my favourites is Buckingham’s (2020) claim that Structured Word Inquiry does not teach grapheme-phoneme correspondences — not only do we repeatedly and explicitly highlight the importance of explicitly teaching GPCs in Structured Word Inquiry in multiple published papers, but also, had directly contacted Buckingham on multiple occasions making this same point prior to her publishing this article. For details see: https://jeffbowers.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/blog/buckingham-2020/. Not to be outdone, Ashman in his recent blogpost entitled: “Motivated Reading and other peculiarities” writes that “Structured Word Inquiry is profoundly weird” and then continues:

It is hard to come to any other conclusion but that these comments are made in bad faith, and because of Buckingham, many people now claim that Structured Word Inquiry does not teach grapheme-phoneme correspondences. Thanks. But it is only one of many errors and mischaracterizations of the data and our claims. If I did not actively push back, even more of their followers would have formed a very mistaken impression of my work.

3) When my work is not being mischaracterized, it is just being ignored, with prominent researchers and many others simply repeating the phrase that the science of reading strongly supports systematic phonics and ignoring the problems I have identified. For some fun examples, see: https://jeffbowers.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/blog/key-lesson/

What to do?

So that is the context, and the question is what do you do in these circumstances? If you want a successful career in reading instruction research an obvious solution is to just join the crowd on phonics and don’t rock the boat. Another approach would be to avoid the debate, focus on other things, and let this juggernaut roll. If you are interested in reading, perhaps focus on other things you can add to phonics, but don’t question the basic claim that phonics instruction is necessary. Yet another response (mine) is to fight to get published, understood, and noticed. I’ve explained my reasoning for taking the third approach, but I’m far from sure it is effective.

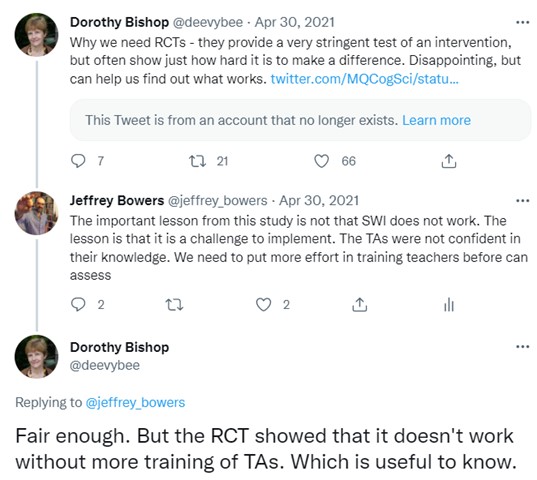

But what about Dorothy Bishop? Bishop has done little or no work on reading instruction, so why did I criticize her in such a public manner? I’ll say two things in my defence. First, Bishop has endorsed the claim that the science supports phonics on several occasions in her blogposts, and recently, commented on a recent paper of mine that failed to show much of an advantage of Structured Word Inquiry compared to an active control condition:

Clearly, Bishop does have an interest in the topic of reading instruction.

Second, and more importantly, much of her recent work is focused on the problems with bad science, and this is arguably the most important example of bad science in the domain of education given the impact the research has had on public policy in England, and the concerted effort to use the flawed evidence to motivate similar policies in Australia and elsewhere. I thought she might be interested in my papers given this context. A third reason I challenged Bishop publicly is that I’m just bloody frustrated that I can’t get anyone to seriously engage with my arguments. The last reason is not a good one I agree.

That all said, Bishop is right, she is not an academic gun-for-hire, and it sure is an unpleasant field if you step out of line. I can understand the reluctance to get involved. So I think I was wrong to get her involved in this mess, and I’ll stick in the future to challenging people who are actively promoting bad science, and hope blogposts like this make neutral readers think twice when they hear the evidence for phonics is overwhelming.

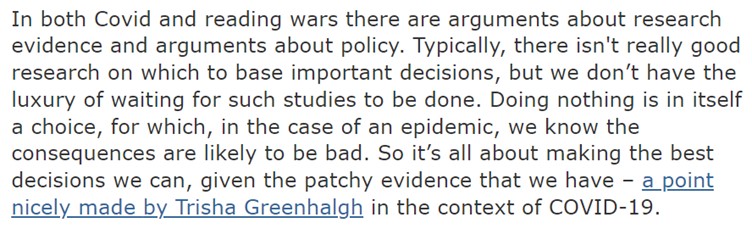

Let me conclude by quoting something by Bishop in her blogpost explaining why she is not engaging in the reading wars. She writes:

I largely agree. But this is good advice for politicians and government officials. When it comes to scientists involved in the science of reading, it is just bad practice to characterize “patchy” evidence as strong evidence because you believe phonics is best policy.

References:

Bowers, J.S. (2020) Reconsidering the Evidence that Systematic Phonics is more Effective than Alternative Methods of Reading Instruction. Educational Psychology Review, 32, 681-705.

Bowers, J.S. (2021). Yes children need to learn their GPCs but there really is little or no evidence that systematic or explicit phonics is effective: A response to Fletcher, Savage, and Sharon (2020). Educational Psychology Review. doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09602-z

Bowers, J.S., & Bowers, P.N. (2021). The science of reading provides little or no support for the widespread claim that systematic phonics should be part of initial reading instruction: A response to Buckingham. doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/f5qyu

Jeffrey S. Bowers and Peter N. Bowers (2018). Progress in reading instruction requires a better understanding of the English spelling system Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27, 407-412. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721418773749

Buckingham, J. (2020). Systematic phonics instruction belongs in evidence-based reading programs: A response to Bowers. The Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 37(2), 105-113.

I want to thank you for challenging the so called “science of reading.” Don’t misunderstand, I totally believe in actual scientific research on reading.

Yes, you are correct that it is very difficult for a “nobody” like me to challenge the established phonics experts. Yet, I keep trying. Like you, I do not support whole language, but there is also evidence that phonics does not work. Sorry, I do not know enough about SWI to make a comment. I use vowel clustering.

I did quote you in one of my blog posts, and I hope that I quoted you correctly. If I did not, please let me know, and I will correct any mistakes.

Reading Wars are Over! Phonics Failed. Whole Language Failed. Balanced Literacy Failed. Who Won? It Certainly Wasn’t the Students.

3/23/2021

No, I’m not making any new friends or changing anyone’s mind, except for the parents and students who I work with. I teach children (who have failed in the classroom with systematic phonics) to read. I teach them to read using vowel clustering, and I have published evidence to prove it. The parents and children are very grateful, but the phonics experts will not even read my books or look at my research.

I am focusing on tutoring this summer. I have a new book using vowel clustering which I used to teach a 15-year-old who had failed for nine straight years in reading. Yes, they used one-on-one systematic phonics tutoring at school. Phonics failed. I taught her to read in 3 ½ years with vowel clustering. If they would just listen to new evidence-based ideas, we can teach students to read.

So, please tell me, how do you change a “closed phonics mind?” I’ve tried and failed.

GROUP-CENTERED PREVENTION – Elaine Clanton Harpine’s Reading Blog (groupcentered.com)

Elaine Clanton Harpine, Ph. D.

clantonharpine@hotmail.com

The question is what do you do in these circumstances?

Here’s a start: Show those of us who teach children how to read exactly how SWI teaches kids to blend and segment sounds. DON’T show us kids talking about words (like the rain family). DON’T show us how to teach the two different pronunciations of the plural ‘s’. Actually show us how to teach kids to put /c/ /a/ /t/ and /d/ /o/ /g/ together BEFORE we go on to discuss the plural form. Don’t talk about the word ‘action’ when the kids can’t even blend /a/ /c/ /t/.

Or rather–DO talk about all these, but not in the context of teaching kids HOW to read. These are all important, but they don’t facilitate blending and segmenting.

Please.